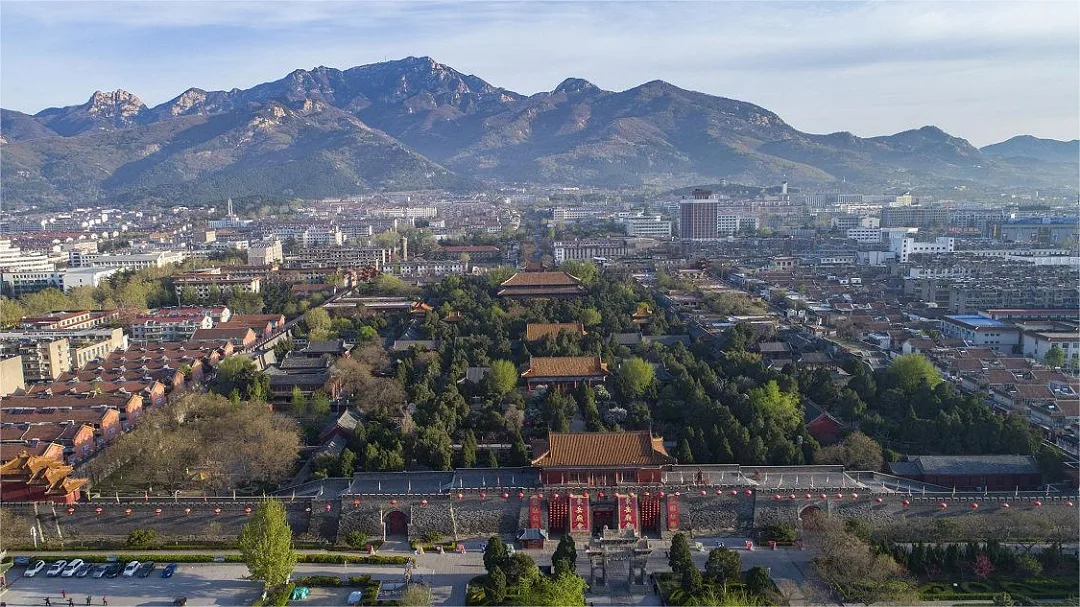

Daimiao Temple (岱庙, Dai Temple), also known as Dongyue Temple (东岳庙), was originally built during the Western Han Dynasty under Emperor Wu. It served as the sacred site where ancient Chinese emperors worshipped the gods of Mount Tai and conducted grand sacrificial ceremonies. Covering an area of 96,000 square meters, the temple is rectangular in shape, with dimensions of 405.7 meters in length and 236.7 meters in width. Its architectural style mirrors that of imperial palaces and cities, surrounded by a perimeter wall spanning over 1,500 meters. Daimiao Temple comprises more than 150 ancient buildings, making it one of China’s four great ancient architectural complexes alongside Beijing’s Forbidden City, the Confucius Mansion and Temple, and the Imperial Summer Resort in Chengde.

Within Daimiao Temple, a wealth of artifacts related to the imperial worship of Mount Tai is preserved, including sacrificial vessels, offerings, artworks, as well as a vast collection of ancient scriptures and Taoist texts. The temple is renowned for its collection of 184 stone tablets and 48 Han dynasty stone carvings, notably featuring the Qin dynasty stone inscriptions, which constitute China’s third largest collection of stone inscriptions after Xi’an and Qufu. Daimiao Temple’s imposing architectural layout, modeled after imperial palaces, represents the highest standard among China’s temple complexes dedicated to imperial worship.

Table of Contents

- Basic Information

- Location and Transportation

- Map of Daimiao Temple

- Highlights of Daimiao Temple

- Vlog about Daimiao Temple

- History of Daimiao Temple

- Other Attractions in Mount Tai Area

Basic Information

| Estimated Length of Tour | 2 hours |

| Ticket Price | 20 RMB |

| Opening Hours | 8.30 – 16.00 |

| Telephone Number | 0086-0538-8261038 |

Location and Transportation

Daimiao Temple is located at 191 Dongyue Street, Taishan District, Tai’an City, Shandong Province, China. To get there, you can take bus 4, 6, 33, 39 North Loop Line, or 39 East Loop Line and get off at Daimiao Stop (岱庙站).

Map of Daimiao Temple

Highlights of Daimiao Temple

Architectures in Central Axis

Double Dragon Pool (双龙池)

Located south of the Yaocan Pavilion Gate, the Double Dragon Pool was constructed in 1880 during the Qing dynasty’s Guangxu reign. Its name derives from the two stone-carved dragon heads positioned at its southeast and northwest corners. The pool measures approximately 3 meters in length from east to west, 2 meters in width from north to south, and stands about 1 meter tall. Its pillars and shafts are intricately adorned with floral stone carvings, and the northern face features a panel inscribed with the calligraphic phrase “龙跃天池” (Dragons Leaping into Heaven Pool). Surrounding the pool are commemorative steles such as the Shuanglongchi Stele and the Wangu Liufang Stele, both erected in 1881 to mark the completion of the water diversion project.

Yaocan Archway (遥参坊)

Situated north of the Double Dragon Pool, the Yaocan Archway dates back to the 35th year of the Qing Emperor Qianlong’s reign (1770). This four-pillar gate-style stone archway spans 9 meters in width and rises 5.8 meters high. Each of its four stone columns is seated on a base adorned with rolling stones, topped by a lintel, fascia board, and ornamental brackets featuring cloud and animal motifs. The archway is inscribed with “遥参亭” (Yaocan Pavilion) on its fascia board, with the date “乾隆三十五年” (the 35th year of Qianlong) beneath it. At the center of the lintel above the middle gate, a design of three flaming jewels (San Bao Huoyan) is depicted, flanked by cloud motifs on the columns’ sides and crowned with heavenly beasts at the top ends. This architectural ensemble, combining stone archways and viewing pillars, showcases a unique style from the Qing dynasty.

Yaocan Pavilion (遥参亭)

Yaocan Pavilion, situated to the south of the Heavenly Street and north of Daimiao Temple, is integral to the ancient rituals performed at Mount Tai. Throughout history, emperors seeking divine favor would first conduct distant ceremonies here. Originally known as “Caocan Gate” during the Tang Dynasty, it evolved into “Caocan Pavilion” during the Song Dynasty. By the Ming Dynasty, it underwent significant expansion with the addition of halls and enclosing walls, transforming into its present form as “Yaocan Pavilion.” The pavilion follows a traditional Chinese courtyard layout, spanning 52 meters east to west and 66.2 meters north to south, covering a total area of 3442.4 square meters. Its central hall, standing on a rectangular platform, measures 10.8 meters wide, 7.75 meters deep, and reaches a height of 7.9 meters. It features a single-eaved, hip-gabled roof with yellow glazed tiles, supported by four columns and five beams adorned with nine ridges. The architectural axis includes the Mountain Gate, Ritual Gate, Main Hall, Platform Pavilion, and Rear Gate, complemented by side halls and chambers.

Daimiao Archway (岱庙坊)

Also known as Linglong Archway, the Daimiao Archway was constructed under the supervision of Shichenyei, the Governor of Shandong Province, during the Qing Kangxi period in 1672. This monumental structure adopts a three-story, four-column layout spanning 9.8 meters wide, 3 meters deep, and standing 11.3 meters tall. The archway is adorned with colossal stone lions at its north and south bases, accompanied by playful smaller lions around. Inscriptions on both sides of the central columns extol the virtues and auspiciousness associated with Mount Tai, emphasizing its significance as a sacred place revered by all nations. The roof features a hip-gabled design with elaborate carvings of mythical creatures like qilins and cranes on the brackets, while dragons ascend the outer edges, symbolizing imperial authority and celestial protection.

Zhengyang Gate (正阳门)

Zhengyang Gate serves as the main entrance to Daimiao Temple, with origins dating back to the Song Dynasty when it was known as Taiyue Gate. In the Ming Dynasty, it was referred to as Yue Temple Gate or Daimiao Gate, and its name has continued through the Qing Dynasty to the present day. Reconstructed in the 1980s on the foundation of a Ming-era structure using Song-era architectural techniques, Zhengyang Gate stands 19 meters tall, with a gate opening 4 meters wide and an interior depth of 17.7 meters. The gate tower atop it, known as Wufeng Tower, rises 11 meters high. Flanking Zhengyang Gate are East and West Side Gates.

Peitian Gate (配天门)

Peitian Gate, the second gate of Daimiao Temple, derives its name from Confucius’ teaching “Virtue matches Heaven and Earth.” Emperors visiting Daimiao Temple would descend from their carriages at this gate, rest briefly behind yellow curtains, purify themselves, and then proceed through Ren’an Gate. Constructed in a single-eaved hip-gabled style, Peitian Gate spans five bays wide and three bays deep. Inside the gate, there were formerly shrines to the Four Symbols of the constellations: Azure Dragon, White Tiger, Vermilion Bird, and Black Tortoise. Flanking the gate are East Three Spirits Hall and West Grand Marshal’s Hall. Guarding the gate are two bronze lions cast during the Ming Wanli period.

Ren’an Gate (仁安门)

Ren’an Gate, the third gate of Daimiao Temple, derives its name from the Confucian principle of benevolence as described in the Analects. Originally constructed in the third year of the Yuan Dynasty’s Zhiyuan era (1266), it was destroyed by fire in the 26th year of the Ming Jiajing era (1547) and subsequently rebuilt multiple times. The gate is built in a nine-ridged double-eaved hip-gabled style, spanning five bays wide and two bays deep. Inside the gate originally housed shrines to the gods of heaven and earth deafness and muteness. It was once connected to surrounding corridors and the Tiankuang Hall, creating a nested courtyard layout centered around the main hall.

Gelao Pool (阁老池)

Gelao Pool, measuring 11.4 meters in length east to west and 7.9 meters wide north to south, is encircled by stone railings. Inside and outside the pool are nine Taihu stones, also known as Linglong stones, each inscribed with historical records, although many inscriptions have become illegible over time. Due to the stones’ resemblance to elderly figures, the pool is named “Gelao Pool.”

Tiankuang Hall (天贶殿)

Tiankuang Hall, also known as Ren’an Hall (仁安殿) or Junji Hall (峻极殿), is the central structure of Daimiao Temple. It was originally built in the second year of the Dazhong Xiangfu era of the Northern Song Dynasty (1009 AD) and has undergone several renovations throughout history. The hall enshrines the spirit of Mount Tai, known as Dongyue Taishan. Tiankuang Hall follows the architectural style of “nine-fold” and features a multi-eaved roof, representing the highest form of ancient Chinese architectural construction. Inside the hall, visitors can admire the monumental Song Dynasty fresco “The Sacred Inspection Tour of Mount Tai,” depicting the grand procession of Mount Tai’s deities, renowned for its vivid and lifelike portrayal of figures and horses. This painting is the only one of its kind in China on this subject matter. The front terrace of the hall has been the site for imperial ceremonies and is flanked by two pavilions housing imperial steles commissioned by Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. Tiankuang Hall, alongside Beijing‘s Forbidden City Hall of Supreme Harmony and Confucius Temple’s Hall of Great Accomplishment in Qufu, is celebrated as one of China’s three great palatial-style ancient buildings.

Rear Imperial Palace (后寝宫)

The Rear Imperial Palace, comprising three sections, dates back to the Dazhong Xiangfu era of the Northern Song Dynasty and has been periodically renovated over the centuries. The Central Imperial Palace, constructed in honor of the goddess “Shu Minghou” of Mount Tai, features a single-eaved hip-gabled roof and is connected to Tiankuang Hall by a corridor. The towering ginkgo trees flanking its east and west sides were planted during the Qing Dynasty.

Houzai Gate (厚载门)

Houzai Gate, initially erected in the second year of the Dazhong Xiangfu era of the Northern Song Dynasty (1009 AD), was known in the Ming Dynasty as the “Hou Zaimen” or “Lu Zhanmen,” serving as the northern gate of Daimiao Temple. Its name “Houzai” derives from the concept in the Book of Changes (Yi Jing), where “Kun is thick and bears all things,” symbolizing the earth’s ability to support all living beings. The gate tower atop Houzai Gate is named Wangyue Pavilion.

Architectures in Western Axis

Tang Huai Courtyard (唐槐院)

Located in the southwest corner of Daimiao Temple, Tang Huai Courtyard, formerly known as Yanxi Courtyard, originally housed the Yanxi Hall dedicated to the deity Yanxi Zhenren. During the relocation of the Nationalist Government of Shandong Province from Jinan to Taian in 1928, this ancient site suffered significant damage. Today, within the courtyard, visitors can explore attractions such as the Tang Huai Cypress, Huai Fragrance Pool, ancient cypress trees providing shade, the Hundred Stele Wall, and the Tang Huai Poetry Stele commissioned during the Qing Dynasty Qianlong era. The northern part of the courtyard contains the remains of the Yanxi Hall.

Yuhua Daoist Academy (雨花道院)

Yuhua Daoist Academy originally served as a residence for Taoist monks. The academy once housed scripture halls, the Huan Yong Pavilion, and the Luban Hall. In 1928, during the relocation of the Nationalist Government of Shandong Province to Taian, the site was converted into a hotel and bathhouse, resulting in severe damage to its ancient buildings and artifacts. In 2007, the academy was repurposed as the Stone Carving Garden of Daimiao Temple, showcasing the essence of Mount Tai stone carvings and calligraphic works by ancient and modern masters from Daimiao Temple’s collection. Today, visitors can still see remnants of the Huan Yong Pavilion and the reconstructed Luban Hall.

Architectures in Eastern Axis

Hanbai Courtyard (汉柏院)

Hanbai Courtyard, situated in the southeast corner of Daimiao Temple, was originally known as Bingling Courtyard due to the presence of ancient cypress trees (Hanbai). These five cypresses are reputed to have been planted during Emperor Wu of Han’s imperial pilgrimage to Mount Tai, notable among them are the “Interlocking Hanbai” and the “Red Eyebrow Axe Mark” cypresses. The courtyard also houses over eighty stone steles and Buddhist scripture pillars from various historical periods. Of particular significance are the imperial steles left by Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty during his ten visits to Mount Tai, many of which are concentrated in this area. To the north of the courtyard stands the Hanbai Pavilion.

Eastern Imperial Seat (东御座)

Located north of the Hanbai Courtyard, the Eastern Imperial Seat, formerly known as the Welcoming Hall, dates back to the Yuan Dynasty and served as a retreat for high-ranking officials and dignitaries. During the Qing Kangxi period, the “Sanmao Hall” was added to enshrine the Sanmao immortals. In 1770, during the Qing Qianlong period, it was expanded into a resting pavilion for imperial visits, known as the Residence Pavilion. This complex comprises the Hanging Flower Gate, Yimen Gate, main gate, main hall, and east-west wing rooms. The Eastern Imperial Seat is the only well-preserved Qing Dynasty palace remaining on Mount Tai today.

Auxuliary Architectures

Corner Towers (角楼)

The Corner Towers of Daimiao Temple are located at each corner of the temple walls, named after the eight trigrams of the Bagua: Gen (northeast), Xun (southeast), Kun (southwest), and Qian (northwest). These towers feature red walls and green tiles, with three layers of eaves and a single-eave, nine-ridge hip and gable roof covered in yellow glazed tiles. Originally destroyed in the 17th year of the Republic of China (1928) during war turmoil, reconstruction efforts saw the completion of Xun Tower and Kun Tower in 1987, followed by Gen Tower and Qian Tower in 1994.

Iron Pagoda (铁塔)

The Iron Pagoda was cast in the 12th year of the Ming Jiajing era (1533). Originally located at Tianshu Temple, it was destroyed during the Anti-Japanese War when Tianshu Temple was damaged. The pagoda originally had eight sides and thirteen levels, cast in separate layers and then assembled. Today, only the bottom four levels remain, each ranging in height from 0.6 to 0.9 meters, with a total height of 3.8 meters. From the fourth level upwards, each side of the pagoda features an arched door with decorative patterns. Inscriptions of donors’ names, birthplaces, and casters are found on the lower three levels.

Bronze Pavilion (铜亭)

Also known as the Golden Que Pavilion (金阙), the Bronze Pavilion was cast in the 43rd year of the Ming Wanli era (1615). Originally housed in the Bixia Pavilion at the summit of Mount Tai, where it enshrined Bixia Yuanjun, it was later moved to Lingying Palace at the end of the Ming Dynasty and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty. In 1972, it was relocated to Daimiao Temple. The Bronze Pavilion now sits on a two-tiered platform, with the lower tier standing at 1.65 meters high and the upper tier resembling a Sumeru pedestal at 1.03 meters high. Made of bronze, the pavilion has a rectangular shape measuring 4.45 meters wide, 3.27 meters deep, and 5.6 meters high. Its architectural style mimics wood structures entirely made of cast bronze, gilded on the outside. The pavilion features a double-eave, nine-ridge hip and gable roof, with chiwen ornaments at the ends of the main ridge and beast-head decorations on the ridges. Circular tiles and drip edges decorate the eaves. Underneath the eaves, a unique architectural feature called “a dou and three sheng dou arch” supports the lower eave purlins, with upturned angle beams stacked on top. Each corner pillar is adorned with connecting brackets and decorative panels. The pavilion’s base consists of basin-style column foundations. Originally, the pavilion’s four walls were equipped with partitioned screens that could rotate and open.

Stone Steles and Carvings (碑碣石刻)

Daimiao Temple houses over 300 ancient stone steles, earning it the nickname “Forest of Steles,” renowned for its collection of calligraphy. Among these treasures is the Qin Dynasty Li Si Stele, engraved in the small seal script by Prime Minister Li Si on the imperial edict of Qin Er Shi Hu Hai over 2,200 years ago. This stele remains a precious artifact of early Chinese calligraphy. Other notable steles include the Han Dynasty’s “Zhang Qian Stele” and “Hengfang Stele” in clerical script style, the Jin Dynasty’s “Madame Sun Stele,” one of the three great steles of the Jin Dynasty, and the unique Tang Dynasty “Double-Bundle Stele.”

The Xuanhe Restoration Inscription Stele (宣和重修泰岳庙记碑), known as the largest tortoise-shaped stele at Daimiao Temple, dates back to the sixth year of the Northern Song Dynasty’s Xuanhe era (1124 AD). Standing 9.2 meters tall, 2.1 meters wide, and 0.7 meters thick, with a tortoise-shaped base measuring 1.9 meters high and 4.8 meters long, this colossal stone monument weighs over 40,000 kilograms. It was meticulously carved by Hanlin academician Yuwen Cuizhong, with the inscription penned by Zhang Zhan, a courtier, and sealed by imperial decree.

Vlog about Daimiao Temple

History of Daimiao Temple

Daimiao Temple, situated at the foot of Mount Tai in Shandong Province, China, has a rich history spanning over two millennia, making it one of the most significant Taoist temples in the country. Originally established during the Western Han Dynasty under Emperor Wu, the temple’s roots trace back to the 2nd century BC when it was dedicated to the worship of Mount Tai, a sacred site revered as the easternmost of China’s Five Great Mountains.

During the Wu Zhou period of the Tang Dynasty, around the 7th century AD, Empress Wu Zetian ordered the relocation of the temple to its present location and renamed it Dongyue Temple, emphasizing its connection to the eastern deity. This relocation marked a new phase in the temple’s significance, linking it more closely with imperial patronage and religious ceremonies.

The Tang Dynasty witnessed significant developments at Dongyue Temple, particularly during Emperor Xuanzong’s reign (725 AD), when the imperial court conducted the Fengshan (worshiping Mount Tai) ritual, elevating the temple’s status as a key site for imperial worship. Subsequent dynasties, including the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing, each contributed to the temple’s reconstruction, expansion, and cultural influence.

Under the Northern Song Dynasty, efforts to expand and refurbish Dongyue Temple were frequent, with major reconstructions and additions such as the Tiankui Hall (later renamed Tiankui Palace) in 1008 AD, emphasizing its role as a center of Taoist ritual and state ceremony. During the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, despite periods of turmoil and destruction caused by wars, the temple continued to be restored and maintained, reflecting its enduring importance as a religious and cultural institution.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties saw extensive renovations and expansions of Dongyue Temple, particularly under the patronage of local governors and imperial decrees. Despite occasional setbacks such as fires and earthquakes, which damaged parts of the temple complex, continuous efforts were made to preserve its architectural heritage and religious significance.

In the 20th century, particularly during the Republican era and subsequent conflicts, Dongyue Temple faced significant challenges, including damage to its structures and cultural artifacts. However, concerted restoration efforts in the mid-20th century and ongoing conservation projects have ensured its preservation as a vital cultural and religious site in modern times.

After climbing Taishan Mountain, I visited Dai Temple. The greenery is impressive and it feels like a park. The ancient trees, which are over a thousand years old, have a fascinating backstory, and it’s really cool under their shade.

The peonies at Dai Temple have bloomed and they are absolutely beautiful!

The flowers at the Dai Temple is blooming now. I passed by and took a few photos; they turned out really well.

Entering Dai Temple before 9 AM ensured a great experience with very few people around.

Daimiao Temple is like a small Forbidden City. It bears traces from the Qin, Tang, Song, Ming, and Qing Dynasties. I spent a full three hours exploring it.

Today, it was super cold at Dai Temple. People who plan to visit should definitely dress warmly! There is a fish pond at the temple, and when I reached out my hand, the fish swam over to me. Later, I waved my hands back and forth by the sides of the pond, and each time, they lined up and swam towards me, haha. The fish at Dai Temple are so much fun!

Enter through the South Gate and exit through the Houzai Gate. The attractions worth visiting are all on the right side, while many buildings on the left have been renovated later. Please note that the ticket for Mount Tai does not include entry to the Dai Temple, and you’ll need to purchase a separate ticket for it.

If you don’t listen to the explanations, you’re just browsing through the place without much depth. The scenery inside is beautiful and perfect for photography.