Kaiyuan Temple (开元寺), located in Quanzhou, is a significant cultural relic in China’s southeastern coastal region and the largest Buddhist temple in Fujian Province. The temple was initially founded during the second year of the Chui Gong period of the Tang Dynasty (686 AD) and was originally named Lianhua Daoyuan (White Lotus Courtyard). It was renamed Kaiyuan Temple in the 26th year of the Kaiyuan era (738 AD). The existing main structures of the temple were built during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The temple spans 260 meters from north to south and 300 meters from east to west, covering an area of 78,000 square meters.

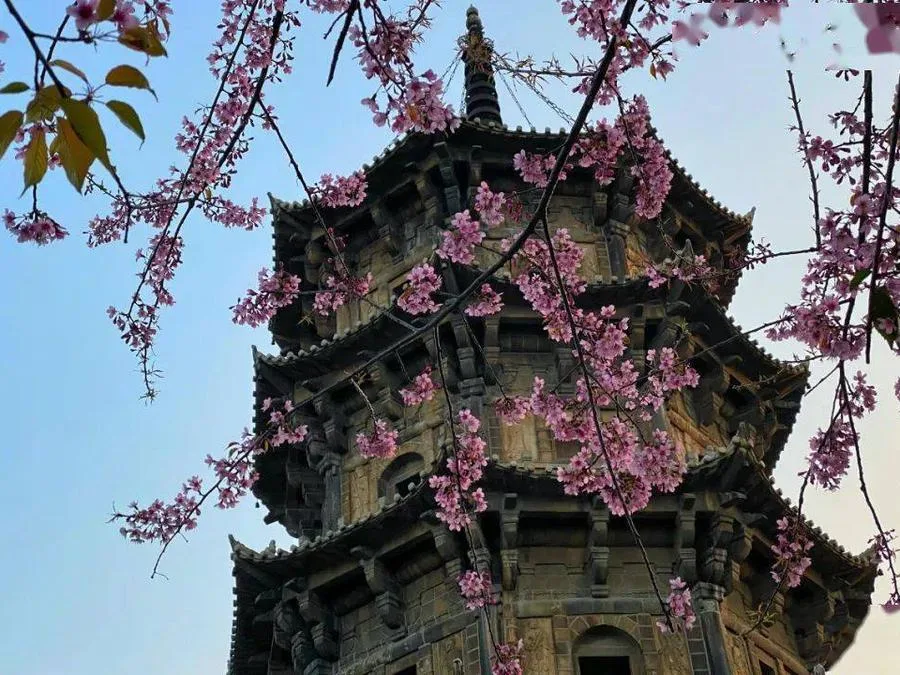

Kaiyuan Temple is one of only three temples in China that retain a precepts altar, the others being Jietai Temple in Beijing and Zhaoqing Temple in Hangzhou. In March, cherry blossoms in shades of light pink and rose pink bloom along the path leading to the West Pagoda, creating a picturesque scene in harmony with the ancient structure.

Table of Contents

- Basic Information

- Location and Transportation

- Map of Quanzhou Kaiyuan Temple

- Highlights of Quanzhou Kaiyuan Temple

- Vlog about Kaiyuan Temple

- History of Kaiyuan Temple

- Other Attractions in Quanzhou Ancient City

Basic Information

| Estimated Length of Tour | 2 hours |

| Ticket Price | Free |

| Opening Hours | 6.30 – 17.30; Last admission: 17.00 |

| Telephone Number | 0086-0595-22383285 |

Location and Transportation

The Kaiyuan Temple is located at 176 West Street, Li Cheng District, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China. To get there, you can take bus 6, 26, 33, 41, 601, or K602 and get off at Kaiyuan Temple West Gate Stop (开元寺西门站)

Map of Quanzhou Kaiyuan Temple

Highlights of Quanzhou Kaiyuan Temple

Heavenly Kings Hall

The entrance gate and the Heavenly Kings Hall are combined into one structure, rebuilt in the 14th year of the Republic of China (1925). Inside the hall, stone columns support a wooden couplet that reads “此地古称佛国,满街都是圣人” (This place was once known as the land of Buddhas, where saints abound). This couplet was composed by Zhu Xi, a prominent Neo-Confucian scholar of the Southern Song Dynasty, and written by the modern monk Hong Yi. Flanking the hall are the figures of the Heavenly Kings according to the esoteric Buddhist tradition, known for their imposing presence and stern countenances, distinct from the typical Four Heavenly Kings found in other temples. They are sometimes humorously referred to as the “Hum and Hah Generals”.

Sutra Library

Originally the Dharma Hall, the Sutra Library was constructed by the monk Liu Jianyi in the 22nd year of the Yuan Dynasty (1285). It has undergone multiple renovations during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, and was reconstructed into a two-story cement and wood-like structure by Monk Yuanying in the 14th year of the Republic of China (1925). The ground floor serves as a place for monks to recite scriptures and worship, while the upper floor houses over 3,700 volumes of various versions of scriptures. Among them are precious texts like the two golden and silver Tripitaka commissioned by King Wang Shenzhi during the Five Dynasties period, as well as the “Lotus Sutra” written in blood by Master Ruzhao of the Yuan Dynasty and palm-leaf manuscripts in Tamil script. These texts represent invaluable treasures of Buddhist literature in China.

The Sutra Library also preserves 32 statues of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Arhats, Heavenly Kings, and divine generals made of jade, bronze, porcelain, and wood from various dynasties ranging from the prosperous Tang Dynasty to the Republic of China. It also houses calligraphy by famous Ming Dynasty calligrapher Zhang Ruitu and modern monk Hong Yi, as well as couplets on wooden plaques.

On the first floor of the Sutra Library, Kaiyuan Temple holds 12 ancient bells dating back to the Southern Song Dynasty, among which the iron bell cast in the 17th year of the Qing Dynasty (1837) with an inscription mentioning the 46 merchants of Lukang who traded with Quanzhou is particularly valuable. This bell provides significant historical insight into the economic relations between Taiwan and Quanzhou during that period.

Mahavira Hall

The Mahavira Hall, also known as the Purple Cloud Hall (紫云大殿), is the main building of Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou, renowned for its historical significance and architectural splendor. Originally constructed in the 2nd year of the Tang Dynasty’s Chuigong era (686 AD), the hall has undergone several reconstructions and renovations during subsequent dynasties, with the current structure dating back to the 10th year of the Ming Dynasty’s Chongzhen era (1637).

The hall spans nine bays wide and six bays deep, covering an area of 1,338 square meters with a double-eaved gable roof that reaches a height of 20 meters. A horizontal plaque hangs beneath the front eaves inscribed with the characters “桑莲法界” (Sanglian Fajie), symbolizing the vastness and purity of the Buddhist realm. Inside the hall, the architectural marvel includes 86 massive stone columns supporting a bracket system that lifts the beams, earning it the moniker “Hall of Hundred Columns.” The ceiling is adorned with 76 dougong brackets, intricately carved with figures like the “Flying Apsaras,” depicting 24 celestial beings combining elements from Buddhist celestial musicians, Christian angels, and traditional Chinese flying figures.

At the center of the hall is the principal statue of Vairocana Buddha, bestowed by imperial decree, known in Chinese Buddhism as Dari Rulai (大日如来), representing the highest deity of Esoteric Buddhism. Flanking this central figure are four great Buddhas added during the Five Dynasties by King Wang Shenzhi when he sponsored the hall’s reconstruction: the Amitābha Buddha from the Western Pure Land, the Bhaisajyaguru Buddha from the Eastern Pure Land, the Mahāsthāmaprāpta Buddha from the Southern Pure Land, and the Avalokiteśvara Buddha from the Northern Pure Land. Together, they are known as the Five Tathāgatas or the Five Wisdom Buddhas. These statues are renowned for their detailed craftsmanship, radiating a serene and compassionate aura with distinct mudras symbolizing teaching, giving, meditation, and protection.

Surrounding these central figures are attendant bodhisattvas and celestial beings such as Mañjuśrī, Samantabhadra, Ānanda, Kāśyapa, Guanyin, Mahāsthāma, Vaiśravaṇa, Guan Yu, Brahmā, and Śakra, totaling ten guardian deities and bodhisattvas. Behind the central shrine, the hall houses the first Sacred Guanyin of the Six Guanyin in Esoteric Buddhism, along with eighteen arhats displaying various postures and expressions.

Ganlu (Sweet Dew) Dharma Altar

Built during the Song Dynasty and extensively rebuilt in the late Ming Dynasty, Ganlu Dharma Altar stands as a masterpiece of Buddhist architecture, revered for its historical significance and intricate design. It features an octagonal, multi-eaved, pointed roof structure with a surrounding corridor, occupying an area of 645 square meters. It is composed of five tiers, with the highest tier housing a wooden statue of the Luóshènā Buddha from the Ming Dynasty. This altar, alongside Beijing’s Jietai Temple and Hangzhou’s Zhaoqing Temple, is recognized as one of China’s three major dharma altars.

Legend has it that during the Tang Dynasty, this site was known for its frequent occurrence of “ganlu” (sweet dew), prompting a monk named Xingzhao to dig a well here, known as the Ganlu Well. In the third year of the Northern Song Dynasty’s Tianxi reign (1019), a dharma altar was constructed over this well, hence its name, the Ganlu Dharma Altar. In the second year of the Southern Song Dynasty’s Jianyan era (1108), Monk Dunzhī restructured the altar according to the norms outlined in the Southern Mountain Catalog, refining it into its current five-tiered structure with strict proportions in height, width, and breadth.

Throughout the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, the altar underwent multiple renovations, culminating in its current form reconstructed in the fifth year of the Qing Dynasty’s Kangxi reign (1666). The pinnacle of the altar features a central coffered ceiling adorned with dougong brackets, intricately layered in a pattern resembling a spider’s web or interlocking patterns akin to brocade weaving, showcasing a complex and refined architectural style. Surrounding the altar, 24 figures of “flying celestial musicians” stand on columns and brackets, each adorned with colorful ribbons and playing various musical instruments such as pipa, erhu, dizi, and xiangban, exuding an air of grace and harmony.

At the highest tier of the altar, the Ming Dynasty wooden statue of Lushena Buddha sits on a lotus pedestal adorned with a thousand lotus petals, each bearing a small Buddha statue measuring 6 centimeters in height. Surrounding Lushena are four Bodhisattvas, as well as statues of Śākyamuni Buddha, Amitābha Buddha, Hanshan, Shide, Avalokiteśvara with a thousand arms, and Weituo generals, totaling 24 Bodhisattva deities. Notably, the statues of the eight great Vajras stand out for their formidable presence, depicted with fierce expressions and imposing stature. Encircling the altar’s waistline are 64 guardian deities, including those protecting the Three Refuges and the Five Precepts, adding further layers of spiritual significance to this revered site.

Two Prominent Pagodas

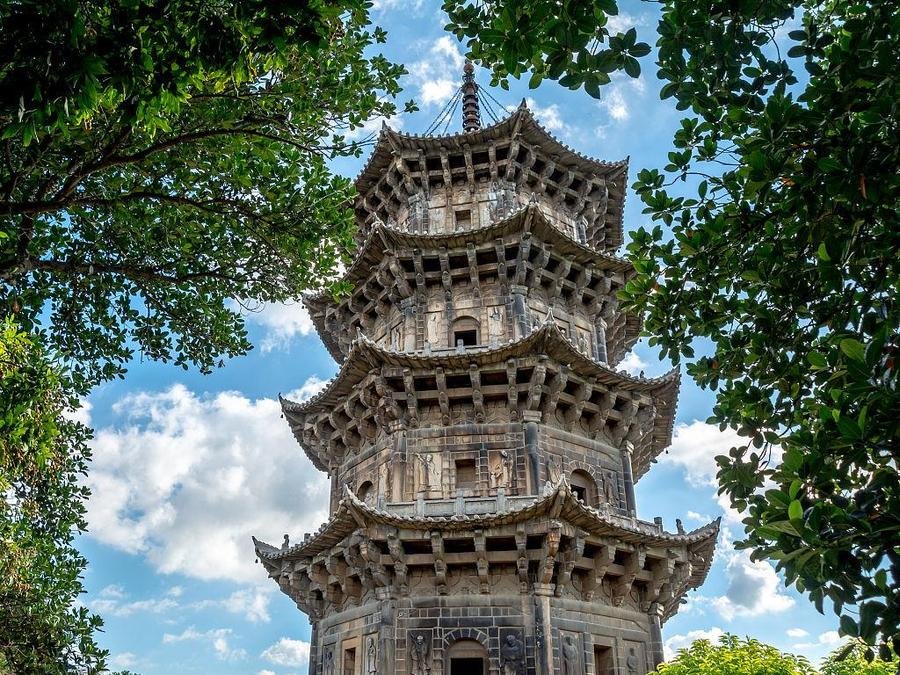

The Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou is adorned with two prominent pagodas flanking its main structure, known as the East and West Pagodas, creating a distinctive “品” shaped layout with the Mahavira Hall at its center. Both pagodas exemplify the architectural grandeur and historical significance of Chinese Buddhist pagodas, having withstood numerous natural disasters over centuries.

East Pagoda

The East Pagoda, also known as the “Zhen Guo Pagoda” (镇国塔), was initially constructed in the sixth year of the Tang Dynasty’s Xiantong era (865 AD) under the supervision of Master Wencheng. Originally a five-story wooden pagoda, it underwent several reconstructions due to damages from earthquakes and other natural calamities. During the Southern Song Dynasty, in the years between 1238 and 1250 AD, it was rebuilt into a seven-story stone pagoda standing at a height of 48.24 meters.

The East Pagoda’s architectural design features a central pillar that runs through the entire structure, providing crucial support for each level. Stone beams at the eight corners of the central pillar connect to the 2-meter thick pagoda walls, enhancing the structural integrity. The walls are meticulously crafted from processed granite, intricately stacked in a crisscross pattern, ensuring both aesthetic appeal and durability. This pagoda, recognized as a pinnacle of stone pagoda craftsmanship, was honored with a spot on China’s “Four Famous Pagodas” postage stamps in 1997.

West Pagoda

The West Pagoda, also called the “Ren Shou Pagoda” (仁寿塔), traces its origins back to the second year of the Five Dynasties’ Liang Dynasty’s Zhenming era (916 AD). Initially a seven-story wooden structure known as the “Wuliang Shou Pagoda,” it was later renamed during the Northern Song Dynasty’s Zhenghe era (1114 AD) to its current title. Like its counterpart, the West Pagoda underwent multiple reconstructions due to damages, eventually being transformed into a stone structure during the Southern Song Dynasty between 1228 and 1237 AD.

Standing at a height of 44.06 meters, slightly shorter than the East Pagoda but of comparable scale, the West Pagoda mirrors the architectural features of the East Pagoda. It showcases the same robust octagonal design typical of Chinese pagodas, emphasizing both structural stability and aesthetic elegance.

Vlog about Kaiyuan Temple

History of Kaiyuan Temple

Kaiyuan Temple, originally founded in the second year of Tang Chugong (686 AD), has a rich and eventful history spanning over a millennium. Legend has it that Huang Shougong, a wealthy merchant in Quanzhou, dreamed of a mulberry tree growing lotus flowers. Inspired by this dream, he donated his mulberry garden to build a temple initially named Lotus Temple.

In subsequent years, the temple underwent several name changes: it was called Xingjiao Temple in 692 AD and Longxing Temple in 705 AD. It wasn’t until the 26th year of Emperor Xuanzong’s reign during the Tang Dynasty (738 AD) that it was officially named Kaiyuan Temple by imperial decree, marking its association with the Kaiyuan era.

Throughout its history, Kaiyuan Temple faced numerous challenges such as destruction and reconstructions. It was rebuilt by Wang Shengu in the fourth year of the Qianning era (897 AD) during the Tang Dynasty after being destroyed. During the Southern Song Dynasty (1155 AD), it suffered another devastation but was soon restored. The Yuan Dynasty bestowed the name “Grand Kaiyuan Longevity Zen Temple” in recognition of its importance.

In the Ming Dynasty, Monk Huiyuan undertook major reconstructions in the 22nd year of the Hongwu era (1389 AD), and further expansions were made during the Yongle era (1408 AD). In the Wanli era (1594 AD), significant repairs were carried out, including the reconstruction of the Mahavira Hall in the 10th year of the Chongzhen era (1637 AD) by General Zheng Zhilong and others.

During the early 20th century, the temple underwent renovations led by various monks and overseen by officials such as the Abbot Zhaodao and Monk Zhuanwu. In modern times, extensive restoration work has been funded by overseas Chinese communities, beginning with the reconstruction of the Mahavira Hall, the main entrance gate, and the Guanyin Hall after 1989.

Today I visited Kaiyuan Temple and discovered that the phoenix tree near the entrance has quietly started to bloom! The one in front of the Zhenguo Tower has only a few flowers open, but they should be in full bloom by next week. The combination of the phoenix flowers and Zhenguo Tower is truly stunning!

During the days I visited, it rained, and although the weather wasn’t great, I was fortunate to avoid the overcrowded scenes described online. The attractions with fewer tourists were quite enjoyable, and the flowers at Kaiyuan Temple were blooming beautifully.

I really like Kaiyuan Temple. The bright green surroundings and the blue sky make it even more beautiful. It would be even better if there were fewer people.

I also love the various wooden carvings inside the temple. The colors are stunning, and when I looked closely, I saw dragons, waves, and clouds. I can’t identify much more, but it looks absolutely gorgeous!

The Kaiyuan Temple in Quanzhou is simply breathtaking! The two stone pagodas are so impressive! There was a ceremony happening inside the main hall, so we couldn’t go in, but even just viewing it from the outside was amazing.

Kaiyuan Temple is located in Licheng District, Quanzhou City. Due to the limited time, I only spent about twenty minutes inside. Unfortunately, I didn’t get to explore it in depth, which is quite regrettable.

After wandering around, the only thing that stuck with me was a “heart” stone at Xiao Jiao (心). The heart’s point is at the bottom, symbolizing that once we let go of that point in our hearts, we can truly feel at ease!

The attractions and food in Quanzhou are quite concentrated. There’s a snack street right near Kaiyuan Temple, but it is somewhat commercialized and the prices are a bit high.

I came in the morning when there were fewer people, and I’m really glad I didn’t go to West Street where it would have been crowded. There are a lot of people taking pictures with hairpins here, so everyone should pay attention to sun protection.