The Forbidden City (紫禁城), also known as Beijing‘s Palace Museum (故宫博物院), is a magnificent historical palace that served as the royal residence for the emperors of China’s Ming and Qing dynasties. Commonly referred to as the Purple Forbidden City, it is located at the heart of Beijing along the central axis. This grand architectural complex is centered around the three main halls, covering a vast area of approximately 720,000 square meters, with a total building area of about 150,000 square meters. The palace complex includes over seventy major buildings and numerous smaller structures. Traditionally, it was believed to house 9,999.5 rooms, though a precise measurement conducted in 1973 revealed that there are actually 8,707 rooms. The Forbidden City stands as one of the largest and most well-preserved ancient wooden structures in the world.

Construction of the Forbidden City began in 1406 during the fourth year of Emperor Yongle’s reign in the Ming Dynasty. It was modeled after the former imperial palace in Nanjing and took fourteen years to complete, with its construction finalized in 1420. For nearly five centuries, it served as the political and ceremonial center of China, housing twenty-four emperors from the Ming and Qing dynasties. In 1925, on the National Day of the Republic of China, the Palace Museum was officially established and opened to the public.

The Forbidden City spans 961 meters from north to south and 753 meters from east to west. It is enclosed by a formidable 10-meter high wall, with a surrounding moat that is 52 meters wide. There are four main gates: the Meridian Gate (Wumen) to the south, the Gate of Divine Might (Shenwumen) to the north, the East Prosperity Gate (Donghuamen) to the east, and the West Prosperity Gate (Xihuamen) to the west. Each corner of the wall is adorned with an elegant watchtower, intricately constructed with a complex design that local legend describes as having nine beams, eighteen columns, and seventy-two ridges.

The Forbidden City is divided into two main sections: the Outer Court (Waichao) and the Inner Court (Neiting). The Outer Court is the ceremonial area where state affairs were conducted. It is dominated by the three great halls: the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihedian), the Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghedian), and the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohedian). These halls were used for major state ceremonies and important official functions. Flanking the central halls are the Wenhua Hall (Hall of Literary Glory) and the Wuying Hall (Hall of Martial Valor), which were used for administrative purposes.

The Inner Court was the residential area of the emperor and his family. Its central structures include the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqinggong), the Hall of Union (Jiaotaidian), and the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunninggong), collectively known as the Three Rear Palaces. These buildings served as the primary living quarters for the emperor and the empress. Behind these halls lies the Imperial Garden (Yuhuayuan). The East and West Six Palaces, located on either side of the Three Rear Palaces, housed the living quarters of the imperial concubines. To the east of the East Six Palaces is the Hall of Imperial Zenith (Tianqiongbaodian), and to the west of the West Six Palaces is the Hall of Military Prowess (Zhongzhengdian), both of which are Buddhist worship halls.

Beyond the Outer and Inner Courts, the Forbidden City also includes the East Route (Waidonglu) and the West Route (Waiwailu), which contain additional buildings and structures. The Forbidden City, with its rich history, grand architecture, and intricate details, remains a symbol of China’s imperial past and a masterpiece of traditional Chinese architecture.

Table of Contents

- Basic Information

- Location and Transportation

- Highlights of the Forbidden City

- Vlog about Forbidden City

- Map and Recommended Routes

- Recommend Photography Spots and Tips

- Best Time to Visit the Forbidden City

- Construction of the Forbidden City

- Symbolism in Forbidden City

- Guardian Cats of the Forbidden City

- Mysterious Cold Palace in the Forbidden City

- Ghost Stories about the Forbidden City

- How did the Forbidden City Got its Name

- Useful Tips Summarized from Reviews

- Attractions near the Forbidden City

- Explore Beijing Like A Local

Basic Information

| Website | www.dpm.org.cn |

| Estimated length of tour | over 3 hours |

| Opening hours | 08.30 – 17.00 (April 1st– October 31st) 08.30 – 16.30 (November 1st – March 31st) |

| Ticket price | Adults: 60 RMB (from April 1st to October 31st) 40 RMB (from November 1st to March 31st) Children under 1.2 meters: Free |

| Galleries | Treasure Galley: 10 RMB The Gallery of Clocks: 10 RMB |

Location and Transportation

The Forbidden City is located at No. 4 Jingshan Front Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing, right at the city’s center. To get there, you can choose one of the following ways:

By Bus: Take bus routes 1, 2, 52, 59, 82, 99, 120, 126, Tourist Line 1, Night 17, Night 1, Night 2, or Special Line 2. After alighting at “Tiananmen East” station, walk approximately 900 meters to the Meridian Gate (Wumen)

By Subway: Take Subway Line 1 and get off at the “Tiananmen East” station. From there, walk approximately 900 meters to enter the Forbidden City through the Meridian Gate (Wumen).

Tips: The Forbidden City does not have its own parking facilities, and nearby public parking areas are relatively far away. Therefore, it is recommended to use public transportation rather than driving.

Highlights of the Forbidden City

Four Majestic Gates and Corner Towers

The Forbidden City is surrounded by towering walls and features four majestic gates, each with its own unique characteristics and historical significance. These gates are the Meridian Gate (Wumen), the Gate of Divine Might (Shenwumen), the East Prosperity Gate (Donghuamen), and the West Prosperity Gate (Xihuamen). Additionally, the four corners of the city walls are adorned with distinctive corner towers, adding to the architectural splendor of the palace complex.

The Meridian Gate (午门)

The Meridian Gate, known as Wumen, serves as the main entrance to the Forbidden City. Its unique concave layout forms a central square flanked by wings, making it the grandest and most imposing of the four gates. The gate complex is colloquially referred to as the “Five Phoenix Tower” due to its five-section structure. The central structure is a two-tiered pavilion with a hipped roof, supported by nine bays in width. The central pavilion extends to the east and west with long corridors that lead to four additional pavilions, one at each corner. These structures are interconnected by covered corridors, creating an impressive and cohesive architectural ensemble.

Wumen is the tallest structure within the Forbidden City, symbolizing its importance. Historically, it was the location where the emperor issued decrees and military orders. The central gate was reserved exclusively for the emperor’s use, with rare exceptions: the empress could enter through this gate on her wedding day, and the top three scholars of the imperial examination could exit through it after their success. Other officials and nobles used the side gates for entry and exit – civil officials through the east gate and military officials through the west gate.

The Gate of Divine Might (神武门)

The Gate of Divine Might, originally known as the “Gate of Mysterious Warrior” (Xuanwumen) during the Ming Dynasty, is situated at the northern end of the Forbidden City. The name “Xuanwu” refers to one of the four mythical beasts representing the north. During the reign of Emperor Kangxi in the Qing Dynasty, the gate was renamed Shenwumen to avoid the taboo associated with the original name.

Shenwumen is slightly less grand than Wumen, featuring a five-bay-wide main hall with a surrounding veranda. It is topped with a double-eaved hipped roof, reflecting the high architectural standards of the imperial complex. Unlike Wumen, Shenwumen lacks the extended wings, placing it a grade lower in terms of imperial hierarchy. This gate was commonly used for the daily comings and goings of palace personnel and now serves as the exit of the Palace Museum for visitors.

The East and West Prosperity Gates (东华门与西华门)

The East Prosperity Gate (Donghuamen) and the West Prosperity Gate (Xihuamen) mirror each other on the eastern and western sides of the Forbidden City. Both gates share a similar architectural style and structure. Each gate features a rectangular layout with a red brick platform and white marble base, incorporating three archways with rounded inner shapes and rectangular outer shapes.

Above the platforms of both gates stand imposing gatehouses, each with a five-bay-wide front and a three-bay-deep structure. The roofs are double-eaved and adorned with yellow glazed tiles, emphasizing their royal significance. The gatehouses also feature surrounding verandas, enhancing their grandeur. Outside each gate stands a dismounting stele, indicating that individuals should dismount their horses before entering.

Corner Towers (角楼)

At each of the four corners of the Forbidden City stands a corner tower, known as jiaolou. These towers are 27.5 meters high and are notable for their intricate and elaborate designs, featuring a cross-shaped ridge and multiple eaves. The corner towers are architectural marvels, embodying complex and sophisticated craftsmanship.

The corner towers’ design is said to symbolize the celestial and earthly realms, with their intricate structure featuring nine beams, eighteen columns, and seventy-two ridges. These towers serve not only as watchtowers but also as decorative elements that enhance the overall aesthetic and symmetry of the Forbidden City’s layout.

Buildings in the Outer Court of the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City’s Outer Court is dominated by the three main halls: the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), the Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe Dian), and the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe Dian). These halls are set on a grand I-shaped, 8-meter-high white marble terrace, with Taihe Dian at the front, Zhonghe Dian in the middle, and Baohe Dian at the back.

The terrace is comprised of three overlapping layers, each adorned with white marble balustrades, ornate railings, and dragon-head spouts. The staircases connecting these levels are intricately carved with coiled dragons amidst waves and clouds, known as the “imperial way,” adding to the majestic appearance of the platform.

The terrace spans 25,000 square meters and features an impressive number of marble decorations: 1,415 carved balustrades, 1,460 pillars engraved with cloud and dragon motifs, and 1,138 dragon-head spouts. This extensive use of white marble creates a striking visual effect, showcasing a unique style of ancient Chinese architectural decoration. Not only is this decoration visually stunning, but it also serves a practical purpose: the dragon heads act as drainage spouts.

Ingeniously designed, these structures function as an elaborate drainage system. Small openings carved under the balustrades and at the ends of the dragon heads allow rainwater to flow through. During the rainy season, water cascades from each level of the terrace through these openings and out of the dragon heads, demonstrating a perfect blend of functionality and artistic design.

The Gate of Supreme Harmony (太和门)

The Gate of Supreme Harmony, also known as Taihe Men, is the largest gate within the Forbidden City and serves as the main entrance to the Outer Court. It was initially constructed during the 18th year of the Yongle reign in the Ming Dynasty (1420) and was originally named the Gate of Heavenly Purity (Fengtian Men). In 1562, during the Jiajing Emperor’s reign, it was renamed the Gate of Imperial Supremacy (Huangji Men), and finally, in the second year of Emperor Shunzhi’s reign in the Qing Dynasty (1645), it was given its current name.

The gate is an imposing structure, spanning nine bays in width and three bays in depth, with a total floor area of 1,300 square meters. It features a double-eaved hip roof covered with golden glazed tiles, supported by a white marble base. The beams and rafters are adorned with colorful paintings, known as “hexi” decorative patterns. In front of the gate, a pair of bronze lions stands guard, symbolizing imperial power.

Flanking Taihe Men are two additional gates: the Gate of Virtuous Harmony (Zhaode Men) to the east and the Gate of Loyal Obedience (Zhendu Men) to the west. Historically, Taihe Men was a place where the Ming emperors held court sessions and heard reports. Early Qing emperors continued this practice until it was moved to the Gate of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Men). On September 1644, the first Qing emperor in Beijing, Emperor Shunzhi, issued an amnesty decree from Taihe Men.

Taihe Men Square (太和门广场)

In front of Taihe Men lies a vast square covering approximately 26,000 square meters. The Inner Golden Water River flows from west to east across the square, spanned by five elegant stone bridges known as the Inner Golden Water Bridges. These bridges are notable for their white marble construction and exquisite carvings.

The square is flanked by two rows of covered corridors, referred to as the East and West Wing Rooms. These corridors provide a symmetrical frame to the open space and were used for various official purposes. In the Ming Dynasty, the eastern corridors housed the Hall of Records, the Genealogy Hall, and the Hall of Daily Records, while in the Qing Dynasty, they were repurposed for the Office of Censorate and the Office of Imperial Edicts. The western corridors served as the Hall of Codes for compiling the Ming Codes during the Ming Dynasty and were later used as the Translation Office and the Hall of Daily Records in the Qing Dynasty.

The Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿)

The Hall of Supreme Harmony, commonly referred to as the “Golden Throne Hall,” is the most prestigious and largest hall in the Forbidden City. It was originally built in 1420 and named the Hall of Heavenly Purity (Fengtian Dian). Renamed the Hall of Imperial Supremacy (Huangji Dian) in 1562, it received its current name in 1645 under Emperor Shunzhi’s rule.

Taihe Dian stands as the ceremonial heart of the Forbidden City, where the emperor held grand state events. It has been destroyed and rebuilt several times, with the current structure dating back to the 34th year of Emperor Kangxi’s reign in the Qing Dynasty (1695). The hall is an enormous structure, measuring 11 bays in width and 5 bays in depth, covering an area of 2,377 square meters. It stands 26.92 meters tall, and including its raised platform, it reaches a height of 35.05 meters. The roof corners are adorned with ten mythical creatures, the highest number allowed, symbolizing the hall’s supreme status.

Throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, 24 emperors used the Hall of Supreme Harmony for major ceremonies, including enthronements, imperial weddings, the conferral of titles to the empress, and the appointment of military commanders. The emperor also held annual celebrations here, such as the Longevity Festival, New Year’s Day, and the Winter Solstice, where he would receive homage from civil and military officials and bestow feasts upon them.

The Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿)

The Hall of Central Harmony, situated behind the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), is a square structure standing at 27 meters high. Each side of the hall measures three bays wide and three bays deep, covering a total area of 580 square meters. The hall features a single-eaved pyramidal roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles and topped with a gilded finial. This elegant design symbolizes the central importance of the hall.

Zhonghe Dian served as a preparatory area for the emperor before attending major ceremonies in the Hall of Supreme Harmony. Here, the emperor would pause to rest and practice the ceremonial rituals. It was also the place where the emperor received homage from the cabinet ministers and officials from the Ministry of Rites before proceeding to Taihe Dian. Additionally, before offering sacrifices to Heaven and the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the emperor would review the sacrificial texts (zhu ban) in this hall. On the day of the imperial plowing ceremony at Zhongnanhai, the emperor would inspect the farming tools here.

The Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿)

The Hall of Preserving Harmony, another of the three main halls in the Outer Court, is located behind the Hall of Central Harmony. Standing at 29 meters high, this rectangular hall measures nine bays wide and five bays deep, encompassing an area of 1,240 square meters. Its double-eaved hip roof, covered with yellow glazed tiles, features a central ridge and nine roof ridges in total, known as a hip-and-gable (xie shan) style.

Baohe Dian was the site of the annual imperial banquet for Mongolian princes on New Year’s Eve. It was also the venue for the palace examinations (dianshi), the final stage of the imperial civil service examinations. This hall’s grandiose design and function underscore its importance in imperial ceremonies and governance.

The Pavilion of Literary Profundity (体仁阁)

The Pavilion of Literary Profundity is located on the eastern side of the square in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, facing west. Initially built in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign, it was originally named Wen Lou. It was renamed Wenzhao Ge during the Jiajing Emperor’s reign and finally given its current name, Tiren Ge, at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty.

Standing 25 meters tall, this two-story pavilion is built on an elevated platform and features a hip-and-gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles. The lower level measures nine bays wide and three bays deep. In the Kangxi era, scholars recommended by internal and external ministers were examined in poetry and prose in this pavilion. After its reconstruction during the Qianlong era, the pavilion housed the Imperial Household Department’s silk storage, containing 143 racks for storing silks and embroidered items.

The Pavilion of Spreading Righteousness (弘义阁)

The Pavilion of Spreading Righteousness, standing 23.8 meters high, is part of the complex surrounding the three main halls. It is located southwest of the Hall of Supreme Harmony. Built in the Yongle era and initially named Wulou, it was renamed Wucheng Ge during the Jiajing Emperor’s reign and received its current name, Hongyi Ge, at the start of the Qing Dynasty, symbolizing the promotion of righteousness.

This pavilion features a hip-and-gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles, spans nine bays wide and three bays deep, and has two stories with surrounding verandas. Throughout the Qing Dynasty, Hongyi Ge was used to store gold and silver utensils used in the palace. Today, it serves as an exhibition hall showcasing royal rituals and music.

Central Route of the Inner Court

The Gate of Heavenly Purity (乾清门)

The Gate of Heavenly Purity serves as the main gate of the Inner Court. Originally constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign, it was reconstructed in 1655 under the Shunzhi Emperor. The gate spans five bays in width and three bays in depth, standing approximately 16 meters tall. It features a single-eaved, hip-and-gable roof resting on a 1.5-meter-high marble base surrounded by carved stone railings. Three main doors dominate the gate, flanked by gilded bronze lions.

To the east and west of Qianqingmen are the Inner Left and Inner Right Gates, as well as the offices of the Nine Ministers and the Grand Council respectively. The gate also connects to Jingyunmen and Longzongmen on either side of the courtyard. Qianqingmen is a vital passage between the Outer Court and the Inner Court and was a key site for administrative activities during the Qing Dynasty. Important ceremonies such as “listening to government matters” (御门听政), fasting, and the reception of imperial seals were conducted here.

The Palace of Heavenly Purity (乾清宫)

The Palace of Heavenly Purity, one of the Three Rear Halls, was initially built in 1420. It has been rebuilt multiple times due to fires, with the current structure dating back to 1798 during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor. This palace features a double-eaved, hip-and-gable roof covered with yellow glazed tiles, supported by a single-story marble base. It spans nine bays in width and five bays in depth, with a total area of 1,400 square meters and a height of over 20 meters.

The spacious front terrace is adorned with bronze tortoises, cranes, sundials, and ceremonial grain measures, with gilded incense burners placed in front. The main steps, known as the Danbi, lead directly to Qianqingmen. The Palace of Heavenly Purity was the primary residence for 14 Ming emperors and the early Qing emperors Shunzhi and Kangxi. After the Yongzheng Emperor’s reign, the palace was used to store the secret documents appointing the heir to the throne, placed behind the “Upright and Honest” (正大光明) plaque. This palace also hosted grand banquets for elderly officials during the Kangxi and Qianlong reigns. Today, it is preserved as a display of the imperial lifestyle.

The Hall of Union (交泰殿)

Located between the Palace of Heavenly Purity and the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, the Hall of Union was built during the Jiajing Emperor’s reign in the Ming Dynasty. The hall is square in shape, with each side measuring three bays in width and depth. The main hall contains the throne, above which hangs a plaque inscribed with “Wu Wei” (无为) by the Kangxi Emperor. Behind the throne is a screen with an inscription by the Qianlong Emperor.

The Hall of Union was where the empress received birthday congratulations and stored the twenty-five imperial seals of the Qing Dynasty. Each January, the Astronomical Bureau would choose an auspicious day for the emperor to ceremoniously open the seal boxes and perform rituals. The hall also housed an iron plaque inscribed with the edict prohibiting interference in state affairs by palace staff, established by the Shunzhi Emperor. During the emperor’s wedding, the empress’s certificates and seals were placed on tables within the hall. Before the spring silkworm ceremonies, the empress would inspect the silk farming tools here.

The Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫)

The Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫) is one of the three main palaces located in the rear of the Inner Court in the Forbidden City. Originally constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign, it was rebuilt in 1645 and again in 1655 to mimic the Shenyang Mukden Palace’s Qingning Palace. Facing south and covering a span of nine bays in width and three bays in depth, the palace features a double-eaved, hip-and-gable roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles.

In the Ming Dynasty, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility served as the residence of the empress. However, after the Qing Dynasty renovations, it became a key site for Shamanistic rituals. The central doorway was moved from the main central bay to the east side, and three kangs (heated brick beds) were installed on the southern, northern, and western sides of the palace for ceremonial use.

The palace holds significant historical importance as it was the venue for the wedding ceremonies of emperors Kangxi, Tongzhi, Guangxu, and Puyi. The restoration efforts during the Qing Dynasty preserved much of its original Ming architectural style while integrating Qing influences. Today, the Palace of Earthly Tranquility is displayed as part of the imperial living quarters exhibit, offering visitors a glimpse into the courtly life of ancient Chinese royalty.

The Imperial Garden (御花园)

The Imperial Garden, located directly behind the Palace of Earthly Tranquility, is an exquisite example of classical Chinese garden design. Known as the “Rear Palace Garden” during the Ming Dynasty, it was renamed the Imperial Garden in the Qing Dynasty. Established in 1420, the garden has undergone several renovations but maintains its original layout. It stretches 80 meters from north to south and 140 meters from east to west, covering an area of 12,000 square meters.

The garden’s central structure, the Hall of Imperial Peace (钦安殿), features a double-eaved, hip-and-gable roof and sits along the central north-south axis of the Forbidden City. Surrounding this hall are various pavilions, terraces, and rockeries, creating a picturesque landscape that integrates seamlessly with nature. The garden is adorned with ancient pines, cypresses, bamboo, and rock formations, presenting a year-round verdant scene.

The Pavilion of Imperial Scenery (御景亭)

Perched atop an artificial hill on the eastern side of the Imperial Garden is the Pavilion of Imperial Scenery. This pavilion occupies the site of the former Ming Dynasty Hall of Viewing Flowers, which was transformed into a rockery during the Wanli Emperor’s reign. Paths made of stone lead up the hill to the pavilion, which offers a splendid view of the surrounding gardens.

The Pavilion of Imperial Scenery is square in shape with four pillars and features a hipped roof with upward-curving eaves, covered in green glazed tiles trimmed with yellow glazed edges and topped with a gilded finial. The pavilion is enclosed by carved marble railings and its interior ceiling is decorated with a painted caisson. Facing south, the pavilion has a throne for the emperor. It served as the site for the emperor and empress to ascend during the Double Ninth Festival on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month, offering them panoramic views of the Forbidden City, Jingshan Park, and the Western Garden.

Western Route of the Inner Court

Hall of Mental Cultivation (养心殿)

The Hall of Mental Cultivation, located on the western side of the Inner Court, south of the Six Western Palaces, was initially constructed during the Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty (16th century). Originally serving as a side hall for the emperor, it became the main residence and administrative center for Qing emperors from the reign of Yongzheng onward. The name “Hall of Mental Cultivation” signifies nurturing the heart and mind. Its convenient location within the palace complex, combined with its versatile layout, made it ideal for the daily routines and governance activities of the emperors. The hall contains various rooms, including the main hall, study, bedroom, and several smaller chambers used for reviewing documents, private discussions, rest, and religious activities. This made it a more practical living and working space for the Qing emperors, reflecting the highly centralized political system of the time.

Notable features of the Hall of Mental Cultivation include the “Diligent and Virtuous” Room, established by Emperor Yongzheng, the “Three Rare Treasures” Room of Emperor Qianlong, and the Eastern Warm Chamber, which served as the site of Empress Dowager Cixi’s regency in the late Qing Dynasty.

Palace of Eternal Spring (长春宫)

The Palace of Eternal Spring, one of the Six Western Palaces, was constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign and underwent major renovations in 1683 during the Kangxi period of the Qing Dynasty. It has been frequently repaired and modified since. In 1859, during the Xianfeng period, the front gate of the palace, Changchun Gate, was dismantled, and the rear hall of the adjacent Qixiang Palace was transformed into a passageway named the Hall of Origin. This change connected the courtyards of the Palace of Eternal Spring and the Qixiang Palace.

The Palace of Eternal Spring features a five-bay main hall with a hip-and-gable roof covered in yellow glazed tiles. Copper turtles and cranes are placed symmetrically in front of the hall. The eastern side hall is named the Hall of Longevity and Tranquility, while the western side hall is the Hall of Continuing Happiness. Each side hall consists of three bays, with verandas extending from their fronts and connected by corner corridors, providing access to the different halls.

Palace of the Universal Happiness (翊坤宫)

The Palace of the Universal Happiness, also part of the Six Western Palaces, was traditionally the residence of imperial concubines. It was constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign. Originally a two-courtyard complex, the late Qing Dynasty saw the transformation of the rear hall into a passageway named the Hall of Harmony, with additional changes made to the ear chambers on the east and west sides, creating access routes. These modifications connected the Palace of the Universal Happiness with the Palace of Gathering Excellence, forming a four-courtyard layout.

The main hall of the Palace of the Universal Happiness is five bays wide, with a hip-and-gable roof covered in yellow glazed tiles, and verandas extending both in the front and rear. The eaves are supported by intricate brackets, and the beams and rafters are decorated with Suzhou-style paintings. The entrance to the main hall is marked by a screen door inscribed with “Prosperity and Brightness,” and the platform in front of the hall features pairs of bronze phoenixes, cranes, and incense burners. The eastern and western side halls are named the Hall of Prolonging Harmony and the Hall of Original Harmony, respectively, each consisting of three bays with gabled roofs covered in yellow glazed tiles.

Palace of Accumulated Beauty (储秀宫)

The Palace of Accumulated Beauty, one of the Six Western Palaces, served as the residence for imperial consorts during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Initially constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign, it underwent extensive renovations in 1884 during the Guangxu Emperor’s rule to celebrate the Empress Dowager Cixi’s fiftieth birthday. The current structure reflects the renovations completed during the Guangxu era. Originally a two-courtyard complex, later modifications saw the removal of the palace gate and surrounding walls, with the rear hall converted into a passageway named the Hall of Harmony, connecting the Palace of Accumulated Beauty with the Palace of the Universal Happiness.

Hall of the Supreme Ultimate (太极殿)

The Hall of the Supreme Ultimate, another of the Six Western Palaces, was built in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign. Initially named the Palace of Everlasting Peace, it was renamed the Hall of Auspicious Propagation in 1535 to commemorate the birth of Zhu Youyuan, the biological father of Emperor Jiajing, who was born here. During the late Qing Dynasty, it was renamed the Hall of the Supreme Ultimate. Originally a two-courtyard complex, later renovations during the Qing Dynasty saw the rear hall converted into a passageway, connecting it with the adjacent Palace of Eternal Spring through corner corridors, forming a continuous gallery.

Palace of Eternal Longevity (永寿宫)

The Palace of Eternal Longevity, one of the Six Western Palaces, was constructed in 1420 during the Yongle Emperor’s reign and was initially named the Palace of Eternal Joy. The front hall of the Palace of Eternal Longevity consists of five bays with a hip-and-gable roof covered in yellow glazed tiles. Inside the hall hangs a plaque inscribed with Emperor Qianlong’s calligraphy, “Virtuous Deeds and Gracious Virtue.” Additionally, the east and west walls feature calligraphy and paintings by Emperor Qianlong. In 1741, Emperor Qianlong ordered that the plaques of all the Eleven Western Palaces be made in the style of the Palace of Eternal Longevity, and once hung, they were not to be moved or replaced.

Palace of Cherishing Splendor (重华宫)

The Palace of Cherishing Splendor, situated to the north of the Western Six Palaces, was originally one of the five palaces in the Qian West area during the Ming Dynasty. In 1733, during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor, it was bestowed upon Hongli, who was then titled “Prince He of the First Rank” and named his residence “Hall of Joyful Benevolence.” After Hongli ascended to the throne, it was renamed the Palace of Cherishing Splendor. Retaining the layout of the Qian West area, the front hall of the palace, known as the Hall of Veneration, features a plaque inscribed by Emperor Hongli himself when he was Prince He of the First Rank, bearing the name “Hall of Joyful Benevolence.” During the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor, the custom of holding poetic tea gatherings in the Palace of Cherishing Splendor during the first ten days of the lunar new year was established as a family tradition. Although it continued sporadically during the reign of the Daoguang Emperor, it ceased after the Xianfeng Emperor’s era.

Palace of Universal Happiness (咸福宫)

The Palace of Universal Happiness is one of the Western Six Palaces, comprising two courtyards. Its main gate, the Gate of Universal Happiness, is adorned with glazed tiles and features a three-bay-wide structure with a roof covered in yellow glazed tiles, distinguished from the other five palaces in the Western Six Palaces area, mirroring the design of the Palace of Sunshine in the Eastern Six Palaces. The rear hall, named the Hall of Mutual Accord, features a sunken partition and a coffered ceiling. The Palace of Universal Happiness served as the residence for imperial consorts, with the front hall used for ceremonial purposes and the rear hall as the sleeping quarters. It housed esteemed imperial consorts such as Noble Lady Lin, Consort Cheng, Consort Tong, and Consort Chang.

Pavilion of Refreshing Fragrance (漱芳斋)

The Pavilion of Refreshing Fragrance was originally the principal building of the Qian West area. Upon Emperor Qianlong’s accession to the throne, the Qian West area was transformed into the Palace of Cherishing Splendor, and the principal building was renamed the Pavilion of Refreshing Fragrance. A theater was also constructed here for gatherings and performances. Shaped like the Chinese character for “work” (工), the pavilion is surrounded by a courtyard enclosed by the front hall, southern quarters, and eastern and western auxiliary halls, connected by covered walkways. During Emperor Qianlong’s reign, important festivals such as the Longevity Festival, Sacred Birthday Festival, Ghost Festival, and New Year’s Eve were celebrated here, with offerings presented to the Empress Dowager in the rear hall, followed by theatrical performances and banquets for royal dignitaries. Even after the abdication of Emperor Xuantong, during the reign of Emperor Tongzhi, the consorts Princess Rongxian and Princess Jingmin continued to reside in the Pavilion of Refreshing Fragrance’s Zhi Lan Chamber, where theatrical performances were held on the Empress Dowager’s birthday until Puyi’s expulsion from the palace.

Eastern Route of the Inner Court

Hall of Ancestral Worship (奉先殿)

The Hall of Ancestral Worship, situated on the eastern side of the Forbidden City, serves as the ancestral temple where the Ming and Qing imperial families offered sacrifices to their ancestors. Originally built during the early Ming Dynasty, it was reconstructed in the Qing Dynasty in 1657 and underwent multiple renovations thereafter. Covering an area of 1225.00 square meters, it features a roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles and intricately painted coiling dragons in gold thread. According to Qing rituals, major sacrifices were conducted in the front hall during significant events like the Lunar New Year and the National Day, while smaller ceremonies were held in the rear hall during birthdays of emperors, empresses, and other important dates.

Palace of Cherished Tranquility (承乾宫)

The Palace of Cherished Tranquility is one of the Eastern Six Palaces, originally named the Palace of Eternal Peace, built in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty. Consisting of two courtyards, the rear hall with five bays and a central entrance served as the residence for noble consorts during the Ming Dynasty and later for imperial consorts during the Qing Dynasty. It housed notable figures such as Empress Dowager Donggo, consort of the Shunzhi Emperor, and Empress Xiaozhuangwen, consort of the Daoguang Emperor.

Palace of Scenic Benevolence (景仁宫)

Built in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty as the Palace of Eternal Peace, the Palace of Scenic Benevolence is one of the Eastern Six Palaces. It features two courtyards, with a five-bay rear hall and a central entrance. During the Ming Dynasty, it served as the residence for imperial consorts. Notably, the Kangxi Emperor was born in this palace in the 11th year of the Shunzhi Emperor’s reign. Empress Dowager Ci’an, mother of the Tongzhi Emperor, and Consort Zhen, consort of the Guangxu Emperor, also resided here.

Palace of Prolonged Happiness (延禧宫)

Originally named the Palace of Longevity, the Palace of Prolonged Happiness is one of the Eastern Six Palaces, constructed in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty. It features three-bay eastern and western side halls in front, with a rear hall consisting of five bays, all topped with yellow glazed tiles. In 1909, a three-story Western-style building called the Water Pavilion was constructed on the original site of the Palace of Prolonged Happiness. Surrounding the Water Pavilion are artificial lakes fed by water from the Jade Spring Mountain. Despite its historical significance, parts of the Palace of Prolonged Happiness were destroyed by bombs during the restoration of Emperor Zhang Xun’s reign in 1917.

Palace of Scenic Radiance (景阳宫)

The Palace of Scenic Radiance, one of the Eastern Six Palaces, stands to the east of the Palace of Clocks and the north of the Palace of Eternal Harmony. Built in 1420 during the Ming Dynasty and renamed in 1535, it originally served as the residence for imperial consorts. However, during the Qing Dynasty, it was transformed into a repository for books. The palace consists of two courtyards, with the main hall facing south and featuring a distinctive roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles. Unlike the other five palaces in the Eastern Six Palaces, the rear hall served as the imperial study, showcasing a five-bay structure with a central entrance and a roof adorned with intricate dragon and imperial seal motifs. The famous “Palace Instructions Scroll,” displayed during the annual imperial festivals, was once housed here.

Palace of Eternal Harmony (永和宫)

Located to the east of the Palace of Cherished Tranquility and to the south of the Palace of Scenic Radiance, the Palace of Eternal Harmony is one of the Eastern Six Palaces. Originally serving as the residence for consorts during the Ming Dynasty and later for imperial consorts during the Qing Dynasty, it hosted the consort of the Kangxi Emperor, Empress Dowager Xiao Gong Ren. Subsequently, it became the residence of Empress Dowager Jinggui and Noble Consort Li during the reign of the Xianfeng Emperor. The palace comprises two courtyards, with the main hall facing south and featuring a five-bay structure. Inside the main hall hangs a plaque inscribed with the imperial phrase “仪昭淑慎 (Yi Zhao Shu Shen),” symbolizing filial piety and virtuous governance.

Palace of Nurtured Happiness (毓庆宫)

Situated between the Hall of Ancestral Worship and the Zhai Palace along the Eastern Route, the Palace of Nurtured Happiness was constructed in 1679 on the site of the Ming Dynasty’s Hall of Fertility. It is a rectangular compound consisting of four courtyards. The palace was originally built for Crown Prince Yunluo during the Kangxi era but later served as a residence for imperial princes. During the Tongzhi and Guangxu reigns, it was used as a study by the emperors, with Emperor Guangxu residing here for a period.

Zhai Palace (斋宫)

Found to the south of the Palace of Nurtured Happiness, the Zhai Palace served as a place of fasting and purification before the ceremonial offerings to heaven and earth. During the Ming Dynasty and the early Qing Dynasty, fasting and purification rituals were conducted outside the palace. The Zhai Palace consists of two courtyards, with the front hall featuring a five-bay structure and a distinctive roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles. It was where the emperor observed fasting rituals before ceremonial events. On fasting days, the emperor and accompanying ministers wore fasting tokens, and no music or alcohol was allowed during the fasting period.

Other Buildings in the Forbidden City

Hall of Martial Valor (武英殿)

The Hall of Martial Valor, dating back to the early Ming Dynasty, stands to the west of the Xiehe Gate in the Outer Court. The main hall faces south, featuring a five-bay structure with a distinctive roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles. Flanked by the Condensing Virtue Hall and the Shining Chapter Hall, the complex includes 63 surrounding halls. In the northeast corner lies the Hengshou Study, while the Yude Hall is situated in the northwest. Initially used for imperial audiences and royal seclusion during the Ming Dynasty, the hall later served as the office of the Regent Dorgon after the Qing Dynasty invaded Beijing.

Hall of Supreme Harmony (皇极殿)

The Hall of Supreme Harmony serves as the centerpiece of the Ning Shou Palace area, originally constructed in 1689 during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor and initially named the Ning Shou Palace. Positioned along the central axis of the Ning Shou Palace area, the hall is elevated on a single-level stone platform. Facing south, it boasts a nine-bay structure, symbolizing imperial authority. Notable features include sundials and gauges, showcasing the emperor’s power. Flanking the central path are twelve hexagonal pedestals, each supporting a double-eaved hexagonal pavilion inscribed with characters symbolizing longevity.

Palace of Compassion and Tranquility (慈宁宫)

Located to the west of the Longzong Gate along the Outer Western Route, the Palace of Compassion and Tranquility was established in 1536 during the Ming Dynasty. In 1769, during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, the main hall was renovated to feature a double-eaved roof, and the layout was finalized. The central hall, facing south, features a seven-bay structure with a double-eaved roof adorned with yellow glazed tiles. The front and rear are connected by corridors, and the façade boasts intricately designed doors and windows. Flanked by brick walls, the palace features a raised platform adorned with four gilded bronze incense burners.

Hall of Literary Profundity (文渊阁)

The Hall of Literary Profundity, situated behind the Wen Hua Hall, serves as a library and was constructed in 1776 during the Qianlong era, modeled after the famous Tianyi Pavilion in Zhejiang Province. The two-story pavilion is topped with black glazed tiles and features green-glazed tile trim, exuding an elegant and subdued atmosphere. It houses the Siku Quanshu (Complete Library in Four Branches) and the Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng (Imperial Collection of Ancient and Modern Books). Apart from being a place for imperial study, it was also open to officials and scholars for research purposes during the Qing Dynasty.

Pavilion of Harmonious Melodies (畅音阁)

The Pavilion of Harmonious Melodies, towering at 20.71 meters, stands in the middle of the Ning Shou Palace area, to the east of the Yangxing Hall. Completed in 1776 during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, it was expanded in the early 19th century with the addition of a stage for theatrical performances. Its distinctive green glazed tile roof, visible even from beyond the palace walls, gives it a prominent presence. The name “Harmonious Melodies” suggests a place for enjoying music to the fullest. The pavilion, facing north, is used for grand theatrical performances during festivals, attracting lively crowds both on and off the stage.

Palace of Longevity and Peace (寿安宫)

The Palace of Longevity and Peace lies north of the Shoukang Palace along the Outer Eastern Route and south of the Yinghua Hall. Originally built during the Ming Dynasty and initially named the Xianxi Palace, it was renamed the Xian’an Palace in 1525 during the Jiajing era. In the early Qing Dynasty, the Xian’an Academy was established here during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor but relocated in 1751 during the Qianlong era. Renamed the Palace of Longevity and Peace in celebration of the Empress Dowager’s sixtieth birthday in 1751, it underwent renovations and had a three-story grand stage added in 1760 for her seventieth birthday celebrations. In 1799, the stage was dismantled, and the theater hall was converted into the Chunxi Hall Rear Annex.

Hall of Nurturing the Nature (养性殿)

Situated within the Yangxing Gate behind the Ning Shou Palace, the Hall of Nurturing the Nature is one of the main buildings in the rear sleeping quarters of the Ning Shou Palace. Built in 1772 during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, it mimics the layout of the Inner Court’s Hall of Nurturing the Heart but on a slightly smaller scale with a unique floor plan. Originally serving as the sleeping quarters for retired emperors, it was adorned with imperial motifs. During the Guangxu era, when the Empress Dowager Cixi resided in the Le Shou Hall, she would take meals in the East Warm Chamber of the Hall of Nurturing the Nature. Following renovations in 1889, the hall’s decor was updated to include Suzhou-style colored paintings, except for the Ink Cloud Room, which retained imperial motifs.

Imperial Concubine Zhen’s Well (珍妃井)

Located within the Zhen Shun Gate at the northern end of the Ning Shou Palace in the Beijing Forbidden City, Imperial Concubine Zhen’s Well was originally an ordinary water well within the palace. It gained its name after Imperial Concubine Zhen was drowned in it on the orders of Empress Dowager Cixi before her flight from the Eight-Nation Alliance invasion in 1900. The well’s opening was covered with a stone slab, and holes were drilled on either side to secure it with an iron rod.

Extensive Collection of Precious Artifacts

The Forbidden City in Beijing houses an extensive collection of precious artifacts, totaling an astonishing 1,862,690 items. Among them, there are approximately one million cultural relics, accounting for one-sixth of China’s total national cultural relics. As of December 31, 2005, the Palace Museum, as a collection unit of China’s cultural relics system, had a total of 109,197 first-class cultural relics, all of which have been documented and filed by the National Cultural Heritage Administration.

Among the 1,330 collection units nationwide that preserve first-class cultural relics, the Palace Museum ranks first with 8,273 items, many of which are unparalleled national treasures. Within some of the palace buildings, comprehensive historical and art galleries, painting galleries, specialized ceramic galleries, bronze galleries, Ming and Qing dynasty arts and crafts galleries, engraving galleries, toy galleries, four treasures of the study galleries, plaything galleries, treasure galleries, clock galleries, and Qing dynasty court ceremonial artifact exhibitions have been established, showcasing a vast array of ancient artistic treasures. It stands as the museum with the richest collection of cultural relics in China.

Since 1949, the Palace Museum has continued to enrich its collection. As of 2017, the total number of cultural relics has reached 1,862,690 items, including 1,684,490 precious artifacts, 115,491 general artifacts, and 7,577 specimens.

Paintings: The Palace Museum boasts a collection of nearly 420 paintings dating back to the Yuan Dynasty and earlier periods. Notable pieces include Gu Kaizhi’s “Illustration of the Goddess of the Luo River” from the Eastern Jin Dynasty, Zhang Zongcang’s “Spring Outing” from the Sui Dynasty, and Yan Liben’s “Procession of the Carriages” from the Tang Dynasty.

Calligraphy: With approximately 310 calligraphy works dating to the Yuan Dynasty and earlier, the museum holds exceptional pieces such as Wang Xianzhi’s “Mid-Autumn Moon” from the Eastern Jin Dynasty and Wang Xun’s “Bo Yuan Tie” scroll.

Porcelain: The Palace Museum’s ceramic collection comprises 350,000 items, including over 1,100 first-class pieces and around 56,000 second-class items. Its collection is particularly notable for ceramics from the Three Kingdoms to the Tang Dynasty, Yuan Dynasty ceramics, late Qing imperial kiln ceramics, palace furnishings, purple clay ware, multi-glaze large ceramics, Qing imperial kiln production materials, ceramics from various dynasties, and archaeological excavations.

Bronze: The museum’s bronze collection exceeds 15,000 items from various dynasties, with approximately 10,000 pieces dating to the pre-Qin period. Noteworthy are the over 1,600 pieces with inscriptions, accounting for over one-tenth of the total number of known and excavated Chinese bronzes worldwide. Additionally, the museum houses over 10,000 coins, 4,000 bronze mirrors, and over 10,000 seals.

Jade: The collection includes 28,461 jade items spanning major historical periods, with a focus on Qing dynasty court jade artifacts. The Palace Museum’s jade gallery is located in the Zhongcui Palace within the eastern six palaces.

Clocks and Watches: Featuring over 1,500 timepieces from China and abroad, the collection includes exquisite pieces from England, France, Switzerland, the United States, and Japan, showcasing the pinnacle of clockmaking from the 18th to the early 20th century. The clock and watch gallery is situated in the Fengxian Hall.

Oracle Bones: The museum houses an estimated 22,463 oracle bone inscriptions, accounting for 18% of the total known oracle bones from the Yin ruins. This collection ranks third after the National Library (34,512 pieces) and the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica in Taiwan (25,836 pieces).

Poetry: In July 2014, the museum discovered two boxes labeled “Qianlong Poetry Manuscripts” containing 28,000 poems by Emperor Qianlong. This discovery, combined with the existing collection of over 17,000 poems, brings the total number of Qianlong’s poems to over 40,000. Emperor Qianlong was known for his fondness for poetry, composing over 40,000 poems throughout his life.

Vlog about Forbidden City

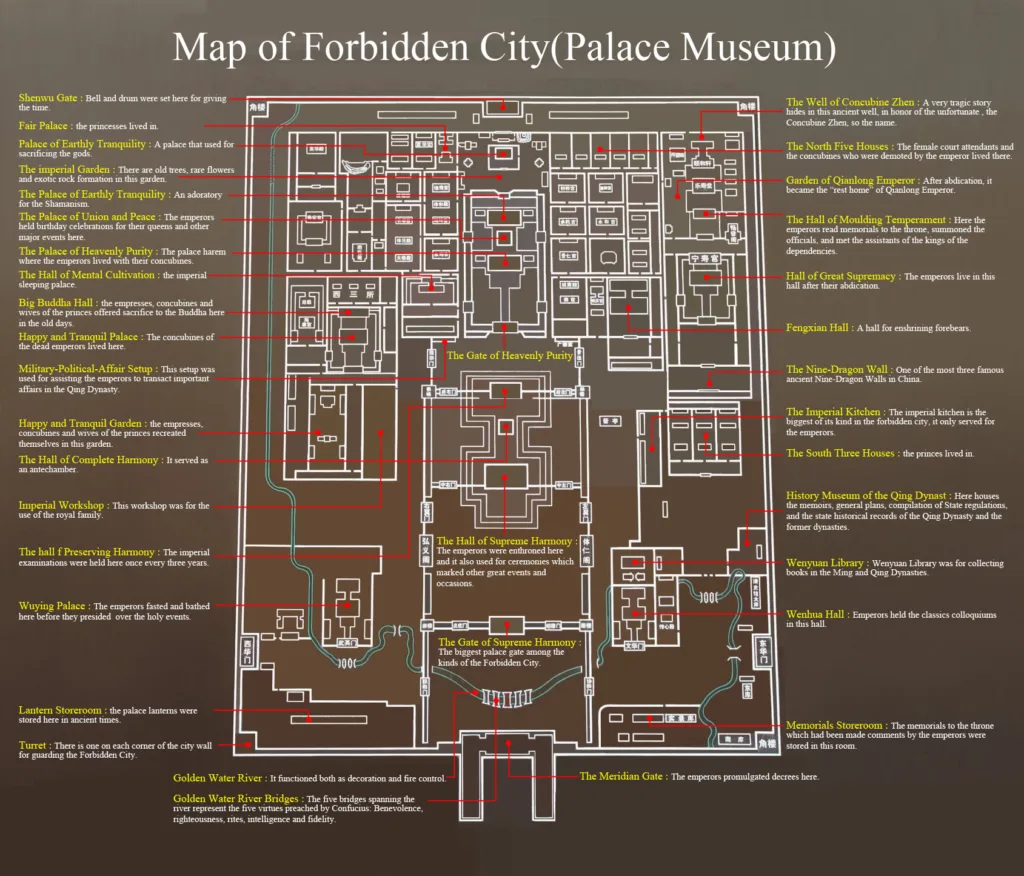

Map and Recommended Routes

One-Day Tour

1. The Meridian Gate(Wu men)

2. “Painting and Calligraphy Gallery” Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian)

3. “Ceramics Gallery” Hall of Literary Brilliance (Wenhua dian)

4. Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihe men)

5. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian)

6. Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian)

7. Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian)

8. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong)

9. Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian)

10. Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong)

11. Hall of Mental Cultivation (Yangxin dian)

12. Area of Six Western Palaces

13. Imperial Garden (Yu huayuan)

14. Area of Six Eastern Palaces

15. “Hall of Clocks” Hall for Ancestral Worship (Fengxian dian)

16. “The Treasure Gallery, Gallery of Qing Imperial Opera” Area of Palace of Tranquil Longevity (Ningshou gong)

17. Gate of Divine Prowess (Shenwu men)

Half-Day Tour

1. Meridian Gate (Wu men)

2. Hall of Martial Valor (Wuying dian): Painting and Calligraphy Gallery

3. Gate of Supreme Harmony (Taihe men)

4. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe dian)

5. Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe dian)

6. Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe dian)

7. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing gong)

8. Hall of Union (Jiaotai dian)

9. Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning gong)

10. Area of Six Eastern Palaces (Dong liugong qu)

11. Hall for Abstinence (Zhai gong)

12. Outer Court of Palace of the Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshougong qu): Treasure Gallery and Stone Drum Gallery

13. Inner Court of Palace of the Tranquil Longevity Sector (Ningshougong qu): Treasure Gallery, Opera Gallery, and the Well of Consort Zhen (Zhenfei jing)

14. Gate of Divine Prowess (Shenwu men)

Recommend Photography Spots and Tips

Photography enthusiasts visiting the Forbidden City will find numerous picturesque spots to capture stunning images. Here are some top locations within the Forbidden City to consider for photography, along with tips to maximize your experience:

1. Jinshui Bridge: Upon entering the Forbidden City from the Meridian Gate (Wu Men), take a right turn and walk up the steps to reach a higher vantage point. Using a wide-angle lens, you can capture expansive views. Early morning provides backlighting, creating a dramatic effect. For fewer crowds, aim to photograph during clearing times.

2. Jingshan Park: Exit the Forbidden City from the North Gate, and directly across the street, you’ll find Jingshan Park. The entry fee is 2 RMB per person, and it’s well worth a visit. From the top of the hill in the park, you can get a panoramic view of the Forbidden City, making it a prime spot for photography. Be prepared for some queues, especially on clear days.

3. Meridian Gate (Wu Men): For a grand entrance shot, it’s recommended to enter the Forbidden City from the East Prosperity Gate (Donghuamen). This will bring you directly in front of the impressive Meridian Gate. On a clear day, the blue sky contrasts beautifully with the architecture, making for a stunning photograph.

4. Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian): The first palace you encounter after passing through the Meridian Gate is the Hall of Supreme Harmony, where ancient officials once gathered. Stand at a distance to capture the grand scale of the hall, particularly during the early morning when there are fewer visitors.

5. Corner Towers of the Forbidden City: Each corner of the Forbidden City features a distinctive tower, iconic to the palace’s architecture. The Northwest Corner Tower is easily accessible from the North Gate. These towers are particularly photogenic, especially during sunset.

6. Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Gong): When photographing the Forbidden City, don’t forget to look up. The intricate details and craftsmanship of the ceilings and eaves are extraordinary and worth capturing. The Palace of Heavenly Purity is an excellent spot for these detailed shots.

7. Yanxi Palace: In autumn, the yellow ginkgo leaves contrast beautifully with the red walls, creating a stunning backdrop. Yanxi Palace is a must-visit spot for capturing the autumn colors.

8. Imperial Garden (Yuhua Yuan): The Imperial Garden features two pavilions with the most beautiful decorative ceilings (caisson ceilings) in China. The way the sunlight filters through can create striking photographs.

Photography Tips:

- Arrive early to be among the first to enter and capture shots with fewer people or wait until just before closing when crowds have thinned.

- Visit on a clear day for the best lighting conditions; the blue sky complements the architecture beautifully.

- If the area is crowded, focus on detailed shots of the buildings, which are equally impressive.

- Explore the palaces on either side of the central axis, as these areas tend to be less crowded.

Best Time to Visit the Forbidden City

Spring (March – May)

Scenic Features: Blooming Flowers: Spring is the season when flowers bloom in abundance within the Forbidden City, especially peonies, apricot blossoms, and peach blossoms. These vibrant flowers decorate the palace grounds with picturesque charm, adding a touch of vitality and poetry to the ancient structures.

Best Time to Visit: Late April to Early May: During this period, the flowers in the Forbidden City are at their most vibrant, making it an excellent time for photography and flower appreciation.

Summer (June – August)

Scenic Features: Cultural Activities: The summer season hosts a variety of cultural events and performances within the Forbidden City, such as court music performances and martial arts displays. These activities provide visitors with deeper insights into the historical and cultural significance of the palace.

Best Time to Visit: Early June to Mid-July: Although the weather can be quite hot, the greenery and cultural activities offer a unique and enriching experience. It is advisable to avoid visiting during the midday hours when temperatures are highest.

Autumn (September – November)

Scenic Features: Vibrant Autumn Foliage: The Forbidden City is transformed by the stunning autumn foliage, with trees adorned in brilliant shades of red and gold. The autumn colors create a beautiful contrast with the ancient architecture, forming a series of picturesque scenes.

Best Time to Visit: Late September to Early November: During this time, the autumn foliage is at its peak. Additionally, the Forbidden City hosts autumn exhibitions and cultural lectures, offering visitors the opportunity to deepen their understanding of historical and cultural heritage while enjoying the scenic beauty.

Winter (December – February)

Scenic Features: Snow-Covered Majesty: The Forbidden City’s ancient structures, covered in snow, exude a unique and timeless elegance. The snow enhances the historic and majestic ambiance of the palace.

Best Time to Visit: Late December to Early January: This period encompasses the Chinese New Year, during which the Forbidden City hosts a variety of ice and snow activities and festive celebrations. The snow-covered landscape is particularly enchanting, but visitors should prepare for cold weather by dressing warmly.

Construction of the Forbidden City

Background and Initial Planning

Beijing, known as Beiping during the early Ming Dynasty, was the fief of Zhu Di, the Yongle Emperor. Following the Jingnan Campaign, in the first year of Yongle (1403), the Minister of Rites, Li Zhigang, and others proposed that Beiping, being the emperor’s place of ascendancy, should be elevated to the status of a secondary capital, similar to how Emperor Hongwu had treated Fengyang. Thus, Emperor Yongle elevated the status of Beiping, renaming it Beijing and designating it the capital, while renaming Beiping Prefecture to Shuntian Prefecture, referred to as “Xingzai” (temporary residence). Simultaneously, the emperor began relocating people to populate Beijing, including various displaced populations, wealthy households from Jiangnan, and merchants from Shanxi, among others.

Construction Begins

In the fourth year of Yongle (1406), Emperor Yongle decreed that the new imperial palace in Beijing should be modeled after the existing palace in Nanjing. This marked the beginning of the construction of the Beijing imperial palace and city walls. The emperor dispatched workers nationwide to procure precious wood and stone, which were then transported to Beijing. This preparation phase alone lasted 11 years.

The procurement of valuable timber, particularly the precious nanmu, involved perilous expeditions into rugged mountains. Many lives were lost in this process, with the saying “a thousand enter the mountains, but only five hundred return” illustrating the high cost in human lives. Similarly, extracting and transporting stone for the palace was arduous. The largest stone slab behind the Hall of Preserving Harmony was quarried from Fangshan, southwest of Beijing. Historical records describe the laborious process: thousands of workers dug wells every mile along the route to draw water and create an ice path during the cold winter months, taking 28 days to transport the stone to the palace.

Additionally, special square bricks, known as “golden bricks,” were fired in Suzhou exclusively for the palace, while tribute bricks were sent from Linqing in Shandong to Beijing.

Key Milestones

In the seventh year of Yongle (1409), using Beijing as his base, Emperor Yongle launched northern military campaigns and began constructing his mausoleum in Changping near Beijing. This decision to build his tomb in Beijing rather than Nanjing signaled his resolve to relocate the capital.

By the fourteenth year of Yongle (1416), the emperor convened his ministers to formally discuss the relocation of the capital to Beijing. Those who opposed the move faced dismissal or severe punishment, effectively silencing any dissent. The following year, construction of the Beijing imperial palace commenced, based on the Nanjing imperial palace as its template.

Completion and Inauguration

In the eighteenth year of Yongle (1420), the construction of the Beijing imperial palace and city walls was completed. The new palace in Beijing was modeled after its counterpart in Nanjing but on a slightly larger scale. The newly constructed Beijing city was a regular square with a perimeter of 45 li (approximately 22.5 kilometers), adhering to the ideal city layout described in the “Kaogong Ji” (Book of Diverse Crafts) of the “Zhouli” (Rites of Zhou).

In the nineteenth year of Yongle (1421), Emperor Yongle issued a decree officially moving the capital to Beijing. He renamed Jinling Yingtian Prefecture to Nanjing and Shuntian Prefecture to the capital, Beijing. However, the six central ministries were retained in Nanjing, each prefixed with “Nanjing” to signify its status as the secondary capital.

Symbolism in Forbidden City

The Forbidden City, a masterpiece of Chinese architecture and culture, served as the imperial palace for the Ming and Qing dynasties. Its design and symbolism reflect profound cultural significance, with each element carrying distinct meanings. Here, we explore the symbolism behind the colors, numbers, stone statues, and dragon motifs within the Forbidden City.

Color Symbolism

Yellow:

- Symbolism: Yellow is the most prominent color in the Forbidden City, especially on the rooftops of important buildings along the central axis. In ancient China, yellow was reserved for the emperor, symbolizing imperial power and nobility.

- Application: Key structures such as the Hall of Supreme Harmony (Taihe Dian), the Hall of Central Harmony (Zhonghe Dian), and the Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe Dian) all feature yellow glazed tiles.

Red:

- Symbolism: Red symbolizes brightness, prosperity, and strength. The red walls of the Forbidden City evoke a sense of grandeur and solemnity while enhancing the majesty of the architecture.

- Application: The southern buildings, including the Meridian Gate (Wu Men), are adorned with striking red walls.

Green:

- Symbolism: Green represents spring, vitality, and growth, suggesting renewal and flourishing life.

- Application: The eastern section of the Forbidden City, primarily the living quarters of the imperial princes, features green tiles.

Black:

- Symbolism: Black symbolizes water and has protective connotations against fire. The predominantly wooden structures of the Forbidden City were vulnerable to fire, and black roofs were believed to offer some safeguard.

- Application: The northern buildings of the Forbidden City often have black tiles.

Gold:

- Symbolism: Gold evokes images of autumn and harvest, symbolizing completeness and abundance. It signifies hope for the empresses and concubines to bear many children, ensuring the dynasty’s continuity.

- Application: The western part of the Forbidden City, where the imperial consorts resided, features gold hues.

Numerical Symbolism

The layout and design of the Forbidden City incorporate significant numbers, particularly “9” and “5”.

Nine (9):

- Symbolism: The number nine is the largest single-digit odd number, symbolizing the highest level of achievement and supreme power.

- Application: Important halls like the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Central Harmony, and the Palace of Heavenly Purity (Qianqing Gong) are designed with nine bays, reinforcing the emperor’s supreme status.

Five (5):

- Symbolism: Five is central and represents balance, encompassing all directions: east, west, south, north, and center.

- Application: The width of these halls often measures five bays. The ratio of 9:5, found in the dimensions of the Forbidden City’s major structures, further emphasizes the concept of imperial supremacy.

Stone Statues Symbolism

Bronze Lions:

- Symbolism: Bronze lions symbolize imperial authority and strength. The male lion, with its paw on a ball, represents the emperor’s dominion over the world, while the female lion, nurturing a cub, signifies the prosperity and continuity of the imperial lineage.

- Application: Bronze lions are placed in front of significant buildings like the Hall of Supreme Harmony and the Palace of Heavenly Purity.

Stone Tortoises:

- Symbolism: Stone tortoises, often paired with cranes, symbolize longevity and stability of the realm. The dragon-headed tortoises, in particular, emphasize the secure foundation of the emperor’s rule.

- Application: A pair of bronze tortoises and cranes can be seen at the entrance of the Hall of Supreme Harmony.

Dragon Symbolism

Dragons are the most dominant and revered symbols within the Forbidden City, representing imperial power and divine authority.

Symbolism:

- Imperial Power: Dragons are mythical creatures that signify the emperor’s divine right to rule. The emperor was often referred to as the “Son of Heaven” or the “True Dragon.”

- Supremacy: The five-clawed golden dragon, found throughout the Forbidden City, underscores the emperor’s exalted status and sovereignty.

- Longevity and Stability: When depicted with tortoises and cranes, dragons also symbolize longevity and the enduring stability of the empire.

Application:

- Architectural Decoration: Dragons are omnipresent in the Forbidden City, from rooftops and ridge tiles to staircases and balustrades. They adorn imperial garments, furniture, and various artefacts, embodying the emperor’s supreme power.

- Artistic Representation: The Forbidden City houses numerous dragon-themed artworks, such as the Nine-Dragon Screen and dragon-carved steps, exemplifying the widespread use of this potent symbol.

Guardian Cats of the Forbidden City

The cats of the Forbidden City, known as the “guardian cats,” add a unique charm to this ancient palace complex and have become an integral part of its culture. These cats are beloved by visitors and play a crucial role in the preservation and daily life of the Forbidden City.

Historical Background

The history of cats in the Forbidden City dates back to the Ming Dynasty. They were introduced to the palace primarily to catch mice and protect the wooden structures from rodent damage. Over the centuries, as dynasties changed, these cats continued to thrive within the palace walls, developing a unique “imperial cat” culture. During the Qing Dynasty, the tradition of keeping cats in the palace persisted, with some emperors, such as Emperor Qianlong and Empress Dowager Cixi, known for their fondness for cats.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Forbidden City was transformed into a museum. The descendants of these imperial cats were welcomed back, and today, there are over 200 cats living in the Forbidden City. These cats are a diverse group, including breeds like Scottish Folds, Persians, and Siamese, among others.

Role and Significance

The cats of the Forbidden City possess unique characteristics such as intelligence, gentleness, and a charming disposition. They play an essential role in protecting the historical artifacts by keeping the rodent population under control, thereby minimizing damage to the priceless collections and ancient structures.

These cats also have their own names and hierarchical system. Male cats are called “little boys,” females are referred to as “girls,” and neutered cats are known as “lords.” Some of the cats are even given titles like “cat steward,” reflecting their esteemed status within the palace grounds. Emperor Qianlong’s painting, “Shadow of the Cat,” depicts ten imperial cats, highlighting the royal affection for these feline guardians and illustrating the cultural significance of cats in the imperial court.

Daily Life and Visitor Interaction

The cats are frequently spotted in areas like the Treasure Gallery, Jingren Palace, and Wenhua Hall. Visitors can often see them roaming freely, adding to the enchanting atmosphere of the Forbidden City. The best time to observe these cats is around 4 PM, during their feeding time, when they gather for their meals.

Mysterious Cold Palace in the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City, the imperial palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, is a complex and expansive architectural wonder with various buildings serving different purposes. One intriguing yet mysterious aspect often mentioned in historical and literary contexts is the concept of the “Cold Palace” (冷宫). Though the term evokes a vivid image, there isn’t a specific, officially designated Cold Palace within the Forbidden City.

What is Cold Palace

The term “Cold Palace” refers to the secluded and neglected quarters within the palace where disfavored concubines and sometimes princes were confined. In the feudal society of ancient China, the emperor held absolute power, including over his concubines. When a concubine fell out of favor or committed a mistake, she would be sent to the Cold Palace as a form of punishment or isolation.

No Fixed Location: The Cold Palace was not a formally designated building but a flexible concept. Its location varied according to the emperor’s decisions and the concubine’s circumstances.

Secluded and Dark: Typically, the Cold Palace was situated in the most remote and gloomy parts of the Forbidden City to ensure the concubine’s isolation and to serve as a form of punishment.

Harsh Living Conditions: The conditions in the Cold Palace were often harsh, with dilapidated, damp, and poorly maintained structures lacking essential facilities.

Instances of Cold Palaces

Yanxi Palace (延禧宫):

- Location: Situated on the eastern route outside the core area of the Forbidden City, far from where the emperor resided.

- Historical Background: Yanxi Palace gained the reputation of a Cold Palace as it often housed disfavored concubines. During the Daoguang era, it was home to Tean Concubine and, at times, sheltered up to four or five concubines in cramped and neglected conditions.

Qianxi Palace (乾西宫):

- Historical Background: During the late Ming Dynasty under Emperor Tianqi, Concubine Li was sent to Qianxi Palace after offending the powerful eunuch Wei Zhongxian. She remained there for four years. Additionally, Concubine Ding and Concubine Ke were also confined there, marking it as a Cold Palace of that era.

Northern Three Palaces (北三所):

- Location: North of Jingqi Pavilion, now collapsed, located near Zhenfei Well.

- Historical Background: In the Guangxu era of the Qing Dynasty, Concubine Zhen was confined in the Northern Three Palaces after displeasing Empress Dowager Cixi, leading to her tragic end in the well. This area is considered a Cold Palace due to these events.

Why Not Open to the Public

Historical Significance: The Cold Palaces, as places of confinement and punishment, hold many untold secrets and tragic stories. Preserving these sites while protecting the dignity and historical narrative of the individuals confined there means keeping them closed to the public.

Safety Concerns: Many buildings designated as Cold Palaces have fallen into disrepair, posing significant safety hazards. To ensure visitor safety, these areas are kept off-limits.

Maintenance Challenges: Post-Qing Dynasty, financial constraints have made it challenging to maintain even the main palace structures, leaving the remote and deteriorated Cold Palaces even less likely to be restored or opened.

Ghost Stories about the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City, with its labyrinthine corridors and ancient halls, is not only a testament to China’s imperial past but also a repository of ghostly tales that have lingered for centuries. Here are three of the most chilling ghost stories that haunt the minds of those who wander through this historic palace.

The 1992 Palace Maid Apparition

It was a stormy summer night in 1992, with thunder cracking through the sky and rain pounding against the ancient tiles of the Forbidden City. A group of tourists, caught in the unexpected downpour, sought refuge within the palace walls. As they huddled under the eaves, a strange sight unfolded before their eyes.

Through the sheets of rain, the tourists saw a procession of palace maids, dressed in traditional garb, walking gracefully along the red walls. They moved silently, their laughter and chatter eerily audible despite the storm. The visitors, drenched and shivering, watched in stunned silence as the ghostly figures continued their spectral parade. Some brave souls even attempted to capture the scene on their cameras, but the images they reviewed later were blurred and indistinct, adding to the enigma.

The Tragic Spirit of Zhenfei Well

In the heart of the Forbidden City lies a well with a dark and sorrowful history. Known as Zhenfei Well, it was the final resting place of the beloved concubine Zhenfei, who met a tragic end during the tumultuous days of the late Qing Dynasty.

One evening, as the sun set and the shadows lengthened, a night guard patrolling near the well began to hear faint, melancholic music. Intrigued, he followed the sound and was startled to see the shimmering figure of a woman in traditional attire, her hands gently plucking the strings of a guqin. As she played, her eyes seemed to search for something, or someone, lost to time. The guard, frozen in place by fear and awe, could only watch as the apparition slowly faded away, leaving behind only the soft echoes of her music.

Rumor has it that on certain moonlit nights, if you peer into the well at exactly midnight, you might see a pool of water that wasn’t there during the day. Reflected in this water, however, is not your face but the sorrowful visage of Zhenfei herself, eternally searching for peace.

The Ominous Yin-Yang Path

Deep within the Forbidden City lies a path shrouded in mystery and dread, known among the palace staff as the Yin-Yang Path. The path, whispered to be heavily haunted, deters even the bravest from treading it after dark.

There was once a young man, bold and dismissive of ghostly tales, who decided to challenge the legends. One night, under the dim light of the moon, he set out to walk the Yin-Yang Path. As he strode confidently down the deserted lane, a chill ran down his spine. Suddenly, while he was washing rice in preparation for a late meal, he heard a voice behind him. “Are you the one who wants to walk the Yin-Yang Path?” the voice asked, low and almost mocking.

He spun around, but there was no one there. The young man’s heart pounded in his chest as he hurried back to his quarters, his earlier bravado replaced by an all-consuming fear. He never spoke of the incident again, but the story spread, reinforcing the path’s eerie reputation.

How did the Forbidden City Got its Name

The Forbidden City is a translation from the Chinese name Zijincheng, which means purple, forbidden, and city if you separate them apart. Let us look at them one by one.

Firstly, in ancient China, the emperor was referred to as the son of heaven or the son of the Jade Emperor who rules heaven. And according to classic literature and myths, the residence of the Jade Emperor is called the purple palace or Zigong. Therefore, the secular emperor’s place is also dubbed the word purple or Zi to show its supremacy and sacredness.

Secondly, this place got the second word of its name because ordinary people were strictly prohibited from entering the city. Any offenders would be dispelled by the guards stationed at the gates. And if they showed any rebellion, they would be killed on the spot at once. Moreover, people living in the city, including the emperor, concubines, maids, and eunuchs, rarely came out of it, which added to its mystery.

Useful Tips Summarized from Reviews

Advance Reservation: It’s crucial to make a reservation through the official WeChat account of the Palace Museum (“故宫博物院”) at least one week in advance. Same-day tickets are not available, and entry is divided into morning and afternoon sessions. Morning session entry closes at 12:00, while afternoon session entry starts from 11:00.

Audio Guide: Renting an audio guide costs 20 yuan per device. While the signal may not always be strong, it provides a general overview and includes a map of the Forbidden City, which can be helpful for navigation.

Shopping Opportunities: There are numerous cultural and souvenir shops within the Forbidden City offering reasonably priced items. Take your time to explore different stores and compare prices before making a purchase.

Closure Times for Specific Sections: Note that the Treasure Gallery and the Hall of Clocks close at 16:00.

Enjoy Afternoon Tea: Consider indulging in afternoon tea at the Wan Chun Jin Fu Tea House, located in the Kun Ning East Courtyard. With prices ranging from 18 to 58 yuan, the delicacies are beautifully presented, with signature items including peanut pudding, yangmei drink, mung bean soup, and chocolate treats.

Dining Options: For dining, try the Bing Jiao Western Restaurant situated south of the Cining Palace. They offer a variety of beverages including coffee, fruit juice, and milk tea, along with desserts like small cakes and Orleans burgers. The hamburgers and fruit teas are highly recommended.

Entrance Strategy: To enter the Forbidden City quickly, head to the East Prosperity Gate (“东华门”) and walk approximately five to six minutes to the Meridian Gate (“午门”) for security check and entry. Avoiding early morning queues, aiming for entry around 10:00 is advisable.

Exiting the Forbidden City: Keep in mind that the exit is separate from the entrance. You cannot exit from the entrance gate. Instead, leave from the Imperial Garden exit, where you’ll find sightseeing buses available for 10 yuan per person to other attractions like Wangfujing and Drum Tower.

Explore Jing Shan Park: Exiting from the Imperial Garden leads you to Jing Shan Park. It offers stunning panoramic views of the Forbidden City, fewer crowds, and affordable ticket prices. It’s a worthwhile spot for a peaceful stroll and to capture memorable photos.

The Forbidden City is currently undergoing renovations on several of its famous halls along the central axis. However, you can still visit and view several other halls nearby that are open to the public.